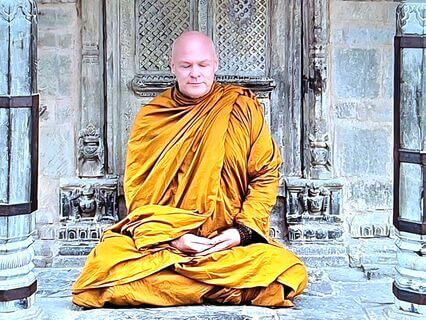

Ajahn Achalo, Spiritual Life Autobiography, Part One

by Ajahn Achalo

Some of my Southeast Asian students requested me to consider writing an autobiography some years ago. At that time, I had to write one in Thai as part of a visa application process, and some of my English-speaking students complained, 'why is there not an English version?' I thought, well, if I was going to write a biography, would it be valuable for myself and for others? And when I was thinking about it, I realized there are some aspects of Buddhist practice which are a little bit difficult to address in a Dharma talk or in a retreat even. But in this more intimate format, you take the hand of somebody and you're bringing them on a journey with you. It then becomes possible to share a different type and depth of experience because it also allows me to take the time to write about subjects by really choosing the words carefully and trying to capture a certain nuance about things.

Transcript

At the request of some of my Southeast Asian students,

They asked me to consider writing an autobiography some years ago.

Some years ago,

I had to write one in Thai as part of a visa application process,

And then some of my English-speaking students complained,

Why is there not an English version?

And then I thought,

Well,

If I was going to write a biography would it be valuable for myself and for others?

And when I was thinking about it,

I realized there are some aspects of Buddhist practice which are a little bit difficult to address in a Dharma talk or in a retreat even.

But in the format of a more intimate,

You take the hand of somebody and you're bringing them on a journey with you,

It becomes possible to explore some of the more subtle and complex,

Delicate,

Painful.

It just becomes possible to share a different type and depth of experience because it also allows me to take the time to write about subjects by really choosing the words carefully and trying to capture a certain nuance about things.

So I thought,

Okay,

If writing such a piece of literature would be of benefit,

Would help people in their Buddhist practice,

Then yeah,

Okay,

I'll do it.

And it's nice to have a bit of a creative challenge as someone who is a teacher.

It's nice to try different approaches to teaching and a creative challenge.

On the more personal level of my personal process,

Reviewing one's life as a Buddhist practitioner,

Sincere Buddhist practitioner,

It's a good opportunity to remember all of the people who benefited one.

I think if a person writes their biography sincerely,

I think,

And honestly,

I think it will be largely an exercise in recognizing the blessings in one's life,

How much help one has received and expressing appropriate gratitude for that.

So in terms of gratitude,

Recognizing blessings and feeling that beautiful quality of gratitude,

Appreciation,

Uditta,

Then it's valuable.

But also in terms of the hard parts,

Have we truly forgiven?

About myself,

When I look at the painful parts in my life,

Have I accepted that that was the working of karma?

Have I forgiven any beings that I may perceive to have harmed me?

And what did I learn?

What did I learn from the blessings?

And what did I learn from the hardships?

Because it's very interesting in life that sometimes we learn more through the difficult times and through working with challenging people.

What's interesting now is when I'm looking back 30 years ago,

When I first began my Buddhist practice,

A generation and a half ago,

I can remember some of those situations were really difficult and really painful.

And when I look back on them now,

I have nothing but appreciation for them.

It's like you can't quite see at the time when you're experiencing something difficult or practicing with something difficult,

Sometimes something that seems impossible,

That it doesn't seem like you're developing a wholesome quality.

Sometimes it doesn't seem like you've been going to get through it.

But being able to look back a couple of decades later,

I can see,

Oh,

Wow,

I really benefited from sticking to that practice or staying in that situation and keeping on trying.

So that's one of the nice nice thing to see that I learned and benefited from the difficult times.

And so I'm probably just going to be a bit of stream of consciousness and just kind of mention some of the things that I've been writing about and,

You know,

Give a bit of a glimpse into life back in Northeast Thailand 30 years ago.

So many of you will know the people who have been my teachers,

Ajahn Jayasaro,

Ajahn Pasno,

Ajahn Sameto,

Ajahn Anan,

And a lot of the people who listen to my Dharma talks also listen to the talks of these monks.

And when I first turned up to Wat Nanachat,

I was on a meditation center in Koh Phangan Island,

And I was wondering what to do with my life.

I was 22,

And I knew I wanted to meditate.

I knew I had faith in Buddhist meditation,

But I didn't know what I was going to do as a lifestyle or a livelihood.

And I met a German man who had been to Wat Nanachat.

In those days,

We did not have a Google search engine,

Did not have Google Maps.

You needed a human being to tell you something,

And you needed to ask people for directions and things like that.

This man,

Fortuitously,

He told me that there is a monastery in Northeast Thailand where there's a training offered for English speakers,

And where no fees are charged,

And the visa is taken care of for one as long as one is able to commit to the routine and the schedule and the training.

So I went up and I had a look.

So when I got out of the tuk-tuk,

I caught the overnight train,

And when I got out of the tuk-tuk at Wat Nanachat,

It was really fascinating because it's a big,

It's a forest,

It's a dark forest,

A monsoon forest with big tall trees.

So I'm getting out of this forest and I'm putting my foot on the ground in Wat Nanachat,

And then I just hear this,

Yo-so-wa-pa-ga-wa.

It was the Uposatha day,

And it was the morning chanting.

The locals were doing their chanting,

And it was like fascinating.

There's maybe about a hundred white-clad little old ladies and old men coming on their lunar observance day.

So I walked,

I put my backpack down outside the Dharma hall,

And I walked into the hall,

And I paid respects to the Buddha statue,

And the Thai monk called a request for the precepts.

So Ajahn Jayasaro was the senior monk.

He got up onto the Tamat,

It's called the Dharma seat,

And he gave the precepts.

So he's saying a line in Pali,

And people are following.

He's saying a line in Pali,

He's saying the following.

But the thing I just wanted to mention is when I went to Wat Nanachat as a 22-year-old,

Ajahn Jayasaro was 36.

So I've known Ajahn Jayasaro since he was a sparkly,

Blue-eyed,

Thin,

Youthful monk.

Because I'd been studying acting and singing,

And I'd studied a lot of cinema,

As studying acting is a good excuse for being able to watch lots of movies.

So I had done that.

And so he had a certain Hollywood appeal as well.

He had this very,

Very chiseled jawline and this very clear,

Sparkly eyes.

And then he was very loquacious,

Eloquent,

Just talking away in Thai like that.

And all of these Thai people just listening,

Peaceful.

I guess he talked for about 40 minutes.

And I was just kind of like,

Whoa,

How is that even possible?

Because I'd only seen the orange robe-wearing monks.

And I walked into this forest.

And there was this,

In those days,

The old salar at Wat Nanachat,

There was this line,

Long line that stretched against the wall.

And there was this whole row of mostly white monks.

And I have to say it,

They looked like impressively miserable.

They were all wearing these dark robes.

And they were sitting in a posture called puppy up with one leg around the side.

But to me,

They all look like they were in full lotus with their knees on the ground.

And they all look like skinny and,

You know,

Depressed.

And I was like,

Whoa,

These guys are hardcore,

Man.

And,

You know,

And I was equally terrified as inspired.

But the monk came and invited me to go and take my meal and then come back and meet Ajahn Jayasaro.

I met Ajahn Jayasaro.

I asked if I would be able to stay.

He said I would.

And I met the guest monk.

And the situation at Wat Nanachat in those days was if you wanted to stay more than three days,

You had to shave your hair and your eyebrows.

So that's a,

That was a kind of a test.

How committed am I to doing this?

But I did it.

I shaved my hair and my eyebrows.

And you have to wear only white.

And you have to keep the schedule.

So that meant 3 a.

M.

Rises,

3.

30 a.

M.

Chanting,

An hour of meditation,

Sweeping leaves while the monks were on arms round.

And yeah,

I could only take it for two weeks.

What was really interesting,

Though,

Is like,

This is why I want to talk about it now.

Here I am,

30 years a monk.

And I just want to relay a little bit about the fact that it wasn't easy.

And I did have to take it in to some degree in baby steps.

What I noticed about myself is that although I struggled,

And although I lamented,

And although I complained the whole time about how hard it was,

And still do,

I did have a certain quality of tenacity,

Dogged tenacity,

Like I just kept doing it,

Complaining all the way.

And,

And that is,

That is what is required.

If you can do it without the complaining,

That's great.

But if you,

If you have to complain a bit,

I think that's okay.

So,

So I could only take it for two weeks.

And part of it was no mattress.

Many,

Many things,

You know,

It's a hot,

Sticky country.

And,

And I was,

I was,

I guess I was probably a bit like a new age hippie.

So I used to like to wear sandalwood oil and lavender oil and patchouli oil.

And I was worked at a vegan macrobiotic cafe.

And,

And all of my friends were beautiful people that smelt nice.

And so the monks bathe several times a day,

Right?

They do.

But in a hot,

Sticky country and sweep leaves and people sweat,

It's like,

Nobody wore deodorant,

Nobody wore cologne.

And we would come to the same room to have afternoon tea together.

And we would get,

Somebody would pour us a cup of coffee and pour us a cup of cocoa.

And they'd just been a work working period.

And,

You know,

It was a bit smelly when we're all in the same room.

And yeah,

It was an adjustment to make.

And we're talking about healthy human sweat.

It wasn't,

It wasn't especially disgusting,

But I just had a sensitive nose.

And I was,

And I was attached to many things,

Including nice smells.

So I went to Chiang Mai,

But the thing is when I got out of the tuk-tuk and put my foot down and stepped into that forest in my heart of heart,

In my,

In my intuitive sense,

I just had this feeling of,

This is the right place.

There was a feeling of like being a ship that was on a rocky,

You know,

In a stormy seas that pulled into a safe port.

That's what it felt like.

And it's like,

Oh,

And when you've been looking for something and you find it,

If you've been looking on an intuitive level,

Or very deeply for something and you,

And you've,

You know,

You've found it,

You have to notice that.

I did notice that,

But like I said,

I could only take it for two weeks.

And then I went to Chiang Mai just because I'd studied some massage,

Some Thai massage and a very funny thing,

A very funny thing happened.

So you have to expect Mara is going to put up a bit of a,

A bit of a fight if someone is thinking of going forth and keeping impeccable standards of virtue.

So I had it in my mind that I was not going to stay in a newish guest house with,

With Western backpackers,

Because although I wasn't really drinking,

Keeping precepts by that stage,

I knew there was some danger if I was lonely.

And if I made new friends and if they invited me out,

There was some danger that I might go out,

Go clubbing or go to the pub or whatever.

So I specifically chose a older looking guest house that had Thai residents and,

Uh,

In the old city,

Little did I know the residents of that guest house were all go-go girls from the local bars.

And they were fascinated with this,

Uh,

Young white man who,

Who did yoga and was studying massage and meditated every day.

They,

They found that very interesting.

So they were like knocking on my door,

Popping in.

And,

Uh,

They did actually invite me out on my birthday.

My 23rd birthday was the last time I went to a nightclub.

The last time I had a beer.

And if I recall,

I actually got on the bar and danced with them.

So that was my,

So at least I left,

I left the scene with a bang as it were.

And I'm almost embarrassed to say it because I learned my moves in the nightclubs of Sydney.

Um,

I was no slacker.

And so I actually got a round of applause for my performance,

But then I took a bow and I never went back,

But I did go back to the monastery and I didn't,

I didn't do anything especially naughty at that time.

I'm just saying that there was,

It was a challenge.

And,

Uh,

Sometimes there was a bang like at two in the morning,

Three in the morning,

I like locked the door,

Light the candles,

Pray,

Chant to the Buddha,

You know,

Just get me back to the monastery.

But it was,

It was a good for me to,

Uh,

It was a good experience in a way because I ended up talking with those young women and I learned a little bit,

You know,

From a sociological point of view,

Anthropological point of view,

Many of them were very nice people from poor rural families.

And,

Uh,

Some of them were like building a new house for mom and dad.

Some of them were putting a brother through university.

They were just really,

They weren't like drug addicted people on the street corner charging for 15 minutes.

They were real sweet human beings who were using the resources they had available to them to try to better themselves and their family.

And,

Uh,

I was happy for that experience because it made me less judgmental,

Have more compassion and,

Uh,

See these human beings,

Many of whom were quite sweet,

But yes,

I hasted back to the monastery and,

Uh,

It was just before Pansa and,

Uh,

I had seven weeks left of my,

Uh,

Three month visa and Ajahn Jayasaro was very kind.

He,

Uh,

He knew I had an interest in possibly going forth.

So he allowed me to take the training as an eight precept anagarika along with a couple of others and to,

That meant I would be going on alms round with the monks and,

Uh,

Attending all of the meetings that the monks attended.

So that meant going on alms round and listening to the rules of training after the alms round.

And then Ajahn Jayasaro was,

Uh,

There was a morning sit.

There was a two hour afternoon sit.

There was an evening sit and Ajahn Jayasaro gave a talk every,

Uh,

Evening for that first month.

And so he was so,

Uh,

Articulate and generous in that regard.

And I was like,

On an intuitive level,

I felt like I was in the right place.

I could see that in terms of,

You know,

You didn't need money to stay there.

If you committed to the training,

You were taken care of.

And I could see that,

Uh,

Many things I saw,

I saw some people who wanted to be monks who came and they had some kind of obstruction.

They may be married,

They may have kids,

They may have a sick parent.

And then I realized about myself,

I didn't really have an excuse.

You know,

I,

I,

The option was there.

And if I walked away,

It was,

Uh,

Yeah,

Something that I would be choosing to do.

And I had a very strong intuition that the causes that I'd laid to have that opportunity in past lives were probably not small causes that,

Uh,

Here I am in Northeast Thailand,

In a monastery where people teach in English,

Where the visa is taken care of at 23 years old.

We used to go in arms around and these old ladies waiting in front of their houses,

Kneeling on the ground.

And they put a little ball of sticky rice in the monk's bowl.

And then they place their sticky rice on top of their head and make their dedications and their prayers.

And I just,

I thought it,

Many of those are laying the causes to have the opportunity to be in taken care of for being taken care of as summoners in the future.

And I just had this really strong sense that I've probably done that for lifetimes.

That's why I'm here.

And if I walk away from this,

It's like,

It wouldn't be the right choice,

But it's not an easy lifestyle to commit to.

It's like 3am rise,

No mattress,

No,

No perfumes,

No,

No fragrance soaps,

No lots of mosquitoes walking barefoot on sharp stones for five kilometers on an empty stomach.

It was,

Yeah,

For someone who had a soft bed and three meals a day.

And also no friendship with women was hard for me in Australia.

In Australia,

You grow up with women kind of being your mates.

It's just in the class,

There are boys and girls,

And you might be sitting next to a boy or you might be sitting next to a girl and the girls are just as likely to be your friend as the boys.

And so I had had big sisters,

I had had good friends who are women,

I'd had plenty of female workmates.

And yeah,

At the bottom end of the line at the Northeast Thailand Forest Monastery,

You do not talk with women,

You do not associate with them.

And so that was,

It wasn't easy to be just completely separated from that.

And a lot of the monks,

At first,

I didn't like them.

I didn't like them.

And,

You know,

There's many different types of monks,

But the Western monks tended in those days to be,

Most of them were university educated and they were kind of heady,

Academic,

Scholastic,

And quite fault-finding.

And so a lot of the conversations were like,

This is right,

This is right,

This is right,

This is wrong,

This is wrong,

This is wrong.

And I kind of,

That wasn't what brought me into the training.

I was looking for peace.

And I had plenty of my own critical opinions as well.

But just the constant critiquing of everything.

They weren't like the fun,

Easy people in the vegan cafe in Sydney and going to the beach with my friends or the movies with my friends.

They were,

They were serious guys.

And so that was a,

That was an acquired taste.

I had to learn to like monks.

And eventually I did,

Because what I realized was,

Well,

They might not be the most lovable,

They might not be the most warm and fluffy people,

But they are the ones who have enough wisdom to know that they have to practice renunciation and they have to be disciplined in order to sow the causes for their liberation.

So they're wise,

They're disciplined,

They have patience,

And how much metta they have is a different,

Is a different subject.

But I learned to appreciate their good qualities.

And so Achintaya Sir was giving a different talk and I was kind of wondering,

Can I do this?

Can I do this?

And he was giving different talk every evening.

And he said a couple of things.

He said,

Lord Buddha had the most merit of any being in the whole universe.

And he had the most abilities.

And he could have done anything he chose to do with vast merits,

Incredible abilities.

And he established the form of a bhikkhu.

And he chose to live within that form himself for 45 years.

And I was just sitting there.

I had great faith in the Buddha.

I was very grateful for his meditation methods for giving me a little bit more peace and a direction,

A refuge.

And I just,

That really struck me as I,

Oh,

Wow.

Yeah,

Well,

Okay,

The Buddha chose to live within this form.

And this form comes from the purified,

Is an expression of a purified and liberated mind.

These are the conventions that he felt were helpful for liberation.

And there was just that sense of,

Oh,

Oh,

No,

I have to do this.

So it wasn't a kind of a hurrah,

Hurrah,

Great joy,

Great joy,

Kind of a great,

Let's be a monk.

It wasn't like that.

It was,

I can't really see anything else that I want to commit to that would give me genuine happiness.

And this is,

Is an option for me.

And I can't see that I can walk away from it.

So I kind of,

It felt like something in me died.

Something in me died during that seven weeks.

And it was like,

You are no longer capable of being a lay person.

It might have been an option before,

But it's not an option now.

And that doesn't mean I wasn't going to keep kick and scream and cry all the way.

It just meant,

It just meant I didn't have a choice anymore.

And with regards all the other rules,

Because we don't just have the 227 rules of the monks.

Lompocha added a whole bunch of extra rules.

We call these core what.

So there's all sorts of things.

The way you carry your monk's bag,

The way you put it down,

The way you walk,

The way you enter rooms,

What you do when you enter rooms,

What you do when you leave rooms,

How you relate to monks who are senior to you.

There is a,

There's a right and a wrong way to do everything.

Every little aspect of your life is,

Is within a very tight container.

And so the other thing that Ajahn Jayasaro said was,

You know,

I lived with Ajahn Chah.

I have confidence that Ajahn Chah was a contemporary Arahant.

He was,

He was someone who had liberated his mind,

Just like the Buddha had liberated his mind.

And these rules that he recommends,

These are coming from a pure liberated mind and Arahant disciple of the Buddha.

And again,

I was just kind of like,

Oh no,

That means I have to keep them.

A lot more rules.

So anyway,

My visa was coming to an end and I had to go back to Australia,

But something happened like,

This was going,

An ongoing challenge for me was that my mind became more sensitive than,

Than the sensitivity increased before the equanimity.

Ajahn Anand was able to help me understand that a bit later when I met him and I'd never felt at home in Australia.

I remember,

I remember just feeling like this is no,

I'm not critiquing my family,

Good people,

But I just,

I just,

I remember being at the dinner table,

Looking left,

Looking right as a child and just thinking,

Who are these people?

That was,

That was my experience.

And when I was in school,

You know,

Wandering around the playground,

Going into class,

I just had this sense of,

This is the wrong place.

It was just,

It's a very strange thing to describe,

But from the age of about six or seven,

I was just kind of like,

No,

Wrong place,

Wrong people.

And I didn't know where the right place was.

I didn't know where the right people were.

I didn't know that,

But I just knew where I was,

Wasn't right.

And so that was,

And that was a bit painful.

So there I was at,

In Thailand and there I was at Wat Ngar Chad and it felt right.

It felt like,

Yeah,

This is where you're supposed to be.

And as hard as it might be,

This is what you're supposed to do.

So I went back to Australia and my mind missed Thailand so much that when I woke up in the morning and opened my eyes,

I was already crying.

The ache for the place that I'd felt a connection with and felt that I loved and felt was the right place.

As the very first conscious moments I had,

There was grief about missing it.

I'm like,

Wow,

How am I going to,

How am I going to get it together to work and save up another ticket and get back there?

And so I,

That was not easy.

Because as I'd said,

As a child,

I'd felt like it was the wrong place after spending time in Thailand and being in the monasteries and doing retreats,

Coming back,

Then it really felt like not the right place.

And I'm not saying that people can't practice in Australia.

Of course they can.

But in those days,

There wasn't much around in terms of infrastructure.

There weren't many monasteries and 30 years ago.

And yeah,

Living in the inner city was a lot of different energies around.

And my mind missed the peace of the forest and missed the monastery.

So I got it together and paid off a debt and saved up the money.

And I was back at Wat Nanachat within,

I think,

Eight weeks.

And then Ajahn Jayasaro and Ajahn Pasano used to take turns being the abbot.

They'd give each other a break.

Ajahn Pasano had been on a retreat in Chidhurst Monastery for a year.

And Ajahn Jayasaro was going to go on a retreat himself for a year.

So Ajahn Pasano came and took over.

So when I went back to Wat Nanachat the second time,

Ajahn Jayasaro was leaving and Ajahn Pasano took over.

I took the eight precepts with Lompopasano.

I'm trying to remember what his age was now.

He was 46.

Lompopasano was 46 years old.

And his last year in Thailand was my first year.

His last year at Wat Nanachat was my first year at Wat Nanachat.

And I became his attendant monk.

So that meant,

That gave me the opportunity to draw quite close to him.

And I just reflect on this because I think I had tremendous good fortune to meet Lompopasano at that time.

Apparently Lompopasano,

Before that retreat in Chidhurst,

Had been quite a fierce man,

Not very patient.

And he would admit this himself,

That he wasn't always skillful,

Lost his patience and could be a bit fierce.

Certainly very strict,

But a bit harsh.

And in Chidhurst he had had some insights into the value of met loving kindness and the the need for loving kindness.

And he'd returned to Wat Nanachat as a more benevolent,

Loving,

Kind of a chilling out older man.

And so I met that Ajahn Pasano and I was the attendant of that Ajahn Pasano.

And this was enormously helpful because,

So I'll just give you a little bit,

It's a bit like being a butler,

Being a monk's personal attendant.

It's a bit like being a butler.

You would have to be at his kuti at 3.

15am,

Take his bag and his sitting cloth,

His sitting cushion,

His outer robe to his seat where he was going to meditate,

Set everything up for him.

So that he comes,

Kneels down,

Puts his outer robe on his bowels,

Everything he needs is there.

At the end of the chant and at the end of the sit in the morning,

You're there by his side when he gets up,

You fold up his sitting cloth,

You take his bag,

You take his outer robe,

Take his robes to the inner sala,

You set his seat up for the meal.

When he comes to go on his alms round,

You literally put his robe over his shoulder.

Then you move in front of him,

Kneel down and you're doing up his robe clips.

Then you take his bowl and your bowl and you have to be where the alms round officially starts before he gets there.

You hand him his bowl.

After the alms round,

You receive his bowl and you rush back to the monastery so that when he gets back to the monastery,

You are on your knees,

Ready to wash his feet the moment he,

The moment he,

The moment he gets there.

Now the meal,

This was,

This was particularly challenging was there was one meal a day,

Very strict and Arjan Pathano ate his meal in 12 minutes.

And he was a smaller man than I was.

And so he would eat his meal.

And there was this,

There was a tradition that you had to wait for the monk before you to take his first mouthful before you could take yours.

So Arjan Pathano was eating one,

Two,

Three,

I was way down the end,

It was about 20 monks.

So it may have taken at least a minute before,

Once Arjan Pathano had had his bite before I could have my first bite.

And then I had to finish a minute,

A minute before he finished.

So that I would,

I would be there.

So no,

He finished,

He used to eat his meal in 14 minutes.

That gave me 12 minutes.

So I had to eat my entire meal of the day in 12 minutes.

And so it largely became a practice of trying to swallow without choking food that wasn't chewed very much.

And then,

But that was the hard part.

But the good part was,

You're going to get to know a person very well,

If you're just like,

Always in their face,

You know,

From 315 to the arms around it,

Just always there.

And it's a training in learning to be mindful and aware of other people's needs,

And becoming less selfish.

And,

But it also gives you the opportunity to,

If you have a question,

And if there is a moment to ask your question,

It establishes a closeness,

It's a mentor mentee relationship.

And even with bathing,

The tradition was to be wearing something like a sarong,

A bathing cloth,

I would put a,

I would put warm water in a bucket,

And I would pour water over Lompopasano's head.

And while he soaked himself,

I pour water over his back,

And I would wash his back.

And then he would wash his,

Whatever you call those private bits,

Personal bits,

He would do that.

And then I would just kind of rinse him until all the soap was off.

He would put another,

He would wipe himself,

Wipe himself,

He put another sarong,

And you would pull the other one off.

And then you would wash that.

So you're,

You're even washing this man's underclothes,

Making his bed,

Taking away his rubbish,

And washing his bowl.

So you get very close to,

To him.

And so after the tea time,

Between the period of afternoon tea and the evening meeting,

There was a little bit of time,

And I would give Ajahn Pasno a foot massage.

And so that was often a time where I could ask him questions,

Or express doubts,

Or complain about something.

And Lompopasano was very present,

Very willing to listen.

And so that was a,

That was a very special opportunity.

At the end of the year,

It turned out that he was leaving to go to help establish a Bayagiri with Ajahn Amaro.

And this was a bit painful for me,

Because I had,

I had made a kind of a father-son like relationship.

The difference in age between myself and Ajahn Pasno at that time,

Yeah,

He could have been a father.

It was that kind of feeling.

And so he was going.

And what happened is,

Ajahn Samedo passed through Wat Nanachat.

I think it was 1996.

And Ajahn Samedo's sense of humor,

And his sense of kind of spaciousness of the way he taught meditation,

The sense of just settledness.

He was,

He'd been at the monk's training for so long,

And he was obviously very happy.

And I wasn't very happy.

I was six days and seven that I wanted to disrobe.

And this is something I want to keep coming back to and mentioning,

That it's not easy.

Why did I stick to it?

Because one day in seven,

My mind was more happy,

My mind felt light,

My body felt light,

I had no remorse,

I felt I had a refuge,

I felt I had a direction.

And I knew that that quality of fulfillment,

Contentment would not be there if I went back to my old life.

So it was a trade off.

You either get this deeper serenity,

Contentment for one day a week,

Or you lose it.

And you have to put up for six days a week of missing all the things that you used to be able to do that you can't do anymore.

But then Ajahn Samedo passed through,

And he was,

Yeah,

Just jolly,

And humorous,

And witty,

And very spacious and benevolent.

And then the sangha held a meeting because they were going to choose who was going to be the next abbot of Wat Nanachand.

Nobody volunteered.

And Ajahn Jayasaro said at the time,

I don't really want to do this,

He said.

And then he said,

But I feel like Ajahn Chah would want me to.

And I can't see anyone else capable offering to do it.

So I will do it for a period of five years,

He said.

But I don't want to.

Now I loved Ajahn Jayasaro,

But those words,

I don't want to do this,

Affected me.

I was thinking,

Because with my worldly standards,

It was kind of like to an Australian,

When you hear someone say,

I don't want to do this,

Your next assumption is,

Well,

They're not going to do it very well.

If they really don't want to do it,

They're not going to do it very well.

And I kept,

I was thinking to myself,

Well,

I don't want an abbot who doesn't want to be an abbot.

I don't want a teacher who doesn't want to be my teacher.

I want an abbot who wants to be an abbot.

I want a teacher who wants to be my teacher.

And then,

So I asked Ajahn Sumedho,

If I wanted to go to England,

Would I be welcome?

And he said I was.

So I had some,

At that time,

I completely underestimated Ajahn Jayasaro's nobility.

Just because he said he didn't want to do it,

Doesn't mean he wasn't going to do a good job of it.

This is a,

This is the thing about being a good monk,

Is like,

One does one's duty,

One rises to the occasion,

One does something as a practice.

He was,

I would say,

One of the very best abbots whatnanachad ever had for that period of five years.

But I didn't know that at the time.

What he,

What I heard him say was,

I don't want to do this.

And I,

And I thought in my,

My prickly,

Prickly,

Rebellious youthfulness,

I thought,

Well,

I don't want you either.

So,

And,

But it actually worked out rather well for me,

Because at that time,

When I went to Amaravati,

Well,

No,

It was a bit dark first.

This is the thing,

Trials and tribulations.

I'm calling my biography,

This Precious Human Life,

Ten Thousand Joys,

Ten Thousand Sorrows.

And you will see this,

This is a recurring theme.

There's the good bits and the hard bits,

The painful bits and the pleasant bits.

And so I was thinking,

I'm going to go and live with Ajahn Sumedho,

Because he's humorous and warm and fuzzy and friendly,

Exudes well-being.

So I land in Hertfordshire in the middle of January,

And I've never experienced a genuinely cold winter before.

And I'd never experienced an eight hours a day of sunshine country.

So it was cold,

And it was dark,

And it was damp.

And all the trees had lost their leaves,

And they looked dead.

And the sky was this sleety gray.

And I hated it.

So you need,

You need to understand that I spent a lot of time on the beach in Australia.

So my sense for the right amount of sunshine is like Australian amount of sunshine.

And anything less than that is like depressing.

So landing in England in the middle of winter was like,

Oh my God,

What have I done?

And they were a bit,

You know,

The heating bill was quite expensive.

So they're a bit stingy with how much electricity you could use.

So you can never quite get your room to be warm,

You know,

And yes.

And then there's the English people themselves,

Of course,

But I better not say too much.

But enough said.

I made some very nice friends in England.

So anyway,

I started,

I landed there,

And I didn't know anybody except Arjun Sumedho.

And it was winter retreat time,

And people were trying to practice noble silence.

So if I started to get these kind of dark moods,

And I was in a very dark place.

So this,

This is challenging.

If your own mind starts to have dark moods,

And your external environment is dark and cold,

I perceive that being Australian,

I perceive that as hostile.

And,

But yet we had the morning meeting,

The afternoon meeting,

The actually mid morning meetings,

Afternoon meetings,

There was quite a full schedule for sitting.

So I did start to get a little bit more samadhi,

A little bit more sensitivity,

Combined with the sense restraint of not talking to anybody,

Because I didn't know anybody.

And some full on things started to happen.

Like I,

I had this dream,

Where I saw a very lucid dream where I saw a figure that looked very much like me,

Except that he was much more powerful.

And he exuded qualities like malice,

Contempt,

Hatred,

And a very powerful kind of a sexual energy as well.

He was wearing all leather.

And he had two dogs,

One dog on either side,

And I would call them hounds from hell.

They were like these black dogs with long teeth that had like spiky armor.

And the dogs turned to quicksilver and moved under my feet.

And I started to lose my balance.

And this being that looked like me except hateful and contemptuous and looked at me and he said,

The F word,

He just went,

And I woke up.

I just say,

Oh my goodness,

What was that?

What am I supposed to do with with that experience?

What was that?

What my interpretation in hindsight is that that was my own what you would call kilesa Mara.

That was the karma that I had made with the kilesas that were coming back to put up a bit of a fight.

And they weren't so pleased about me thinking of committing to this training full time.

And so but a couple of days,

It was even worse.

A couple of days later,

It was in this state between sleep and consciousness.

I think I think this was different.

I think this was a Mara Deva,

A black being burst through the door.

And in the middle of the night,

He was streaming this strange eerie yellow color.

And it was just like pure hatred,

Pure hatred just burst through my door and woke me up.

And I actually was able to close the door with my mind.

It's just like,

What what do you what do you do with this?

I had no friends.

I was 23.

I was in the middle of a dark,

Cold winter.

And I'm like,

No,

I need to.

I need to talk with someone about this.

But I was a bit scared as well.

Because what if someone says you're crazy,

You know,

You know,

When else has experienced this,

I hadn't heard other people talking about it.

So I,

My good fortune was that in that year,

Arjun Veeradhammo was attempting to be the abbot of Amruwati.

He was giving it a trial to try to give Lompus Sumedho a break,

Because he loved and respected Arjun Sumedho.

Arjun Sumedho had been doing this for a long time.

So what that meant was everyone,

Most people who know Arjun Veeradhammo know that he's very friendly,

Warm,

Grandfatherly energy.

So he was approachable.

I told him about my experience.

And he said he doesn't experience much of this visual phenomena.

So he said,

You should talk with Arjun Sumedho though,

I'm sure Arjun Sumedho will be able to help you.

And so after the meal,

I asked Arjun Sumedho,

If I could come over and give him a foot massage and have a chat.

And Arjun Sumedho wasn't surprised by it.

He wasn't horrified by it.

He wasn't impressed by it.

But he did say,

He says,

I don't think it's anything to worry about.

He said,

If the if the forces of darkness are objecting to something that you're doing,

It probably means that what you're doing is good.

And he said,

It's probably a sign of your merit.

I wouldn't worry about it.

And I said to him,

Well,

I do feel a bit,

I do feel a bit paranoid.

I feel a bit isolated.

Would it be okay if I popped in and gave you a foot massage on some days and just to have a bit more contact?

And he said,

Sure.

So this was my good fortune was because Lumpur Virudhamo was taking along a lot of administrative duties.

Arjun Sumedho was quite available at that time.

And at that time Arjun Sumedho was 62 years old.

So I used to pop in,

Give him a foot massage and most days.

And we used to go for a walk in the countryside.

He and I would go for a walk,

About a 40 minute walk and come back to the monastery.

And he,

You know,

He did have this grandfatherly energy.

He enjoyed mentoring and encouraging younger monks.

I remember having a conversation with him saying,

I just don't think I'm good enough to be a bhikkhu.

I don't think I'm virtuous enough.

I don't think I have enough accumulated merits.

And he looked at me,

And this is really helpful,

He looked at me and he said,

Nenachalo,

Compared to me at your age,

You are a saint.

And I'm like,

Really?

He's like,

Yes,

Really.

Because he'd been in university in Berkeley back in the day,

Sexual liberation and all that stuff.

I love peace and harmony.

And he did tell me some stories.

I won't repeat them here.

But suffice to say,

He sowed his wild oats and had his experiences.

And this to me was enormously helpful.

This great guru figure who's in front of you,

Who's a abbot and leader of several monasteries,

Who's obviously very radiant,

Didn't start that way.

And the other things,

You know,

Had many opportunities to talk with him over the months.

And he had been in Thailand.

The forest tradition in Thailand in those days had a bit of a,

Quite a kind of a macho,

Willful,

It's not easy.

And so that was another of my doubts.

I just don't know if coming from the suburbs in Australia,

Being a bit of a hippie,

New age hippie,

I don't know if I've got what it takes,

You know.

And he says,

Well,

I think you do.

Because more than being impressive on the outside,

The thing that's most important is your,

Your reflective abilities,

Your kind of inner creativity,

Your ability to use the Buddha's rules of training to train yourself.

And that's not about being macho.

That's not about looking impressive.

That's about being sensitive and reflective and being capable of learning.

And he said to me,

Just looked at me and he said,

You know,

You are very sensitive,

But you also have a really good reflective ability.

The things that you perceive as your strengths now will one day,

He said,

The things that you perceive as your weaknesses now and your challenges,

I believe they will be your gifts if you just stick to this training.

And I think you have what it takes.

So that was enormously helpful,

As you can imagine.

And I was able to do a 10 day retreat with Ajahn Sumedho.

And because they have a meditation center there at Amaravati,

And I was able to do a 10 day retreat.

And I had during that time,

A very interesting meditation experience,

Which was also very helpful.

So I'd met in my year as a novice at Wat Nanachat,

One monk had taken us on a trip to pay respects to several senior monks,

I'd paid respects to Lungta Maha Boa,

Lungpa Ben,

Lungpa Utthai,

Lungpa Khamdun,

He was amazing.

And also I'd met Lungpa Panyawadu,

The most senior English speaking disciple of Ajahn Maha Boa.

I'd been able to ask Ajahn Lungpa Panyawadu,

What do you do with despair?

I often just feel despairing.

What do I do with this emotion?

And he said,

You need to catch it really early before it completely fills the mind and takes over.

He said,

When you're observing the breath in the chest area,

Be mindful of feelings as they arrive,

Arise,

And notice them as they change.

And don't,

Don't try,

Don't let them completely take the space.

There was a very similar teaching to what Lungpa Chah's teaching about sitting in the chair of the mind,

Being aware of guests as they come in,

But not allowing them to take the seat.

Lungpa Panyawadu said,

Catch these things early and then notice the way they change.

And he said,

It's almost like we're looking at the pictures of a movie projector,

And then we're reacting to that.

You need to get back to the projector.

You need to be right where the projector is projecting.

Come into that heart area and notice feelings as they arise,

Change,

Stay for some time,

And cease in that area.

And then he looked at me and he said,

And I have got some very good results from practicing in that way.

So that was very helpful.

You know,

When you,

When you,

When you tell someone I've got this challenge,

I'm experiencing this difficulty,

And they give you a method to practice with that and tell you that they got good,

Good results from working in that way.

That was encouraging.

So I was doing this more spacious type of meditation that Lungpa Samedho teaches,

Listening to the sound of silence.

But I was also kind of watching feelings in that area,

Aware of my breath.

And maybe five days,

Six days into a 10 day retreat,

In the afternoon,

Something very interesting started to happen.

We don't know it.

We don't know it because we experience it most of the time,

The way that thinking that you're a self and grasping at things as being a self affect how we perceive the body and mind.

It's like we're fish,

And we swim in that water,

And we don't recognize water.

But what started to happen was paying attention to these feelings as they arose,

And as they change,

And as they cease in a container of a retreat situation.

The feeling of being a self disappeared from my feet and my legs.

And I didn't even know there was a feeling of being a self there.

I didn't know that.

But what I did notice was that from my waist down,

There was just a perception of legs and feet,

And there was no self there.

And it's something that you have to experience.

And then to really understand what I'm saying,

And I hope some of you have.

What happened next was that that feeling continued to throughout the abdomen,

And then the chest,

And then the arms.

And then it was like this experiences from the head down,

There was awareness of a body,

But there was a no grasping at it as being a self.

And as I continued with the meditation,

There was a strange tension in my face,

And and the feeling of being a self like disappeared through the crown of my head.

And I was sitting there,

There was awareness of breath,

Awareness of a body,

Awareness of sounds,

But there was no self grasping.

And so what then the bell rung,

The end of the session,

And I could not open my eyes,

I could not change my posture,

I could not bow,

I just sat there,

Because there was no one there to to do that.

In that experience,

Everybody left the dharma hall.

I guess it was maybe 10 or 15 minutes later that a more normal habitual perception returned.

And then that experience was enormously helpful,

Because I guess it's what you would call a vipassana jnana,

An insight knowledge.

By just by just paying attention to feelings,

Feelings staying for some time ceasing,

Feelings staying for some time ceasing,

Feelings staying for some time ceasing,

Not feeding any thoughts about liking or disliking,

Thoughts about the past,

Thoughts about the future,

Just seeing feelings stay arising,

Staying for some time ceasing,

Arising,

Staying for some time ceasing.

I wasn't feeding the self-view in a world.

And so the self-view stopped being manufactured for a period of time.

And that deeper part of awareness was able to experience a body and a mind without the self-view present.

And then then I got it on a different level.

This isn't a theory.

When Buddha says it's not self,

He means it.

When Buddha says self-view is a view,

A habitual way of perceiving things which is not the ultimate truth,

He's speaking truth.

When you practice hard enough and consistently enough that you will experience body and mind without the self-view present,

Then you then you get it.

Then it comes back and it's like,

Oh yeah,

Okay.

And then it becomes a story,

That great experience you have,

You know,

The self makes a story out of it,

Goes and tells all sorts of friends.

But once you have experienced something like that,

You do understand the theory more deeply from your own experience.

Because vipassana jnanas,

They occur in a deeper level of consciousness.

So you don't forget it.

You don't forget this experience.

So that was enormously helpful for my faith in Buddha's teachings and faith in the fact that it's possible to be aware and have a body and feelings and not suffer.

So this was the other obvious thing.

It was probably an insight into not-self.

The feeling of grasping as a self completely disappeared,

Wasn't present.

But Lomporanan explains it that when you have an insight into one of the three characteristics,

You see the other two and you experience emptiness.

So in seeing,

In there being no perception of self present,

There was no suffering.

None at all.

And that was extremely instructive because it's like,

Yeah right,

You only suffer when you think it's your pain,

Your pleasure,

Your past,

Your future,

Your worries.

When you grasp the hindrances.

But when the self you isn't there grasping and no one there to suffer.

So it was just a glimpse.

But as I said,

A deep glimpse of something wonderful,

Possible to be conscious and not suffer.

Possible to have a body,

Thoughts and feelings and not grasp.

So that was enormously helpful for my faith.

And then I realized something.

I realized,

Okay,

I am going to commit to this bhikkhu training.

I do feel confident enough to make this commitment.

Now I am.

But I had a kind of an inevitable insight.

If I'm going to do that,

I want to do it in Thailand.

And I miss the forest.

I miss the alms round.

I miss the time alone in the forest.

And so I wrote a letter to Ajahn Jayasaro.

And he wrote back saying,

Yes,

You'll be welcome.

If you get back in time for panca,

You can ordain with your friends.

And so then I had to tell Ajahn Sumedho.

And I think Ajahn Sumedho probably felt a little bit ripped off because he had done,

He had been very kind and generous with his mentoring and give me a lot of time.

And normally the abbot or the senior monk might hope that the junior person then responds with some generous service towards the community or something.

And so,

But I felt all kind of shored up and confident.

And I'm like,

Can I go back to Thailand?

And he gave his blessing.

And the way I see it,

When I look back on it,

Though,

I actually think it's the perfect compliment to your mentor.

If through mentoring you,

He gave me the feeling of being confident to go back and train in the very same places that he trained in the way that he trained,

Then that's,

I think,

A perfect compliment to your mentor.

And although I may not have served or helped that community very much,

I did help others.

And established my own later.

So that relationship with Ajahn Sumedho endured for a long time.

When Ajahn Sumedho would pass through Thailand,

He would invite me to attend his 10-day retreat in Thailand when he taught them to lay people.

So I did that a few times and I did it in America as well.

So he was a very important teacher to me,

As was Lompopassano and as was Ajahn Jayasaro.

So I went back and became a bhikkhu at Wat Nangachat.

I was terrified.

I was terrified.

I was committed and I was terrified.

Which is,

I think,

A good thing.

The thing I was terrified of,

I guess,

Was making bad karma.

You know,

It's like,

One person once said,

Monks have one foot in heaven and one foot in hell.

If you're a good monk,

You're going to heaven and beyond.

If you're a bad monk,

You're going to hell.

There's not much middle ground when it comes to monks,

Because we live off the offerings of others.

So if you abuse that,

There are serious consequences.

And yeah,

So we sewed our own robes in those days,

And we made our own dye from jackfruit wood,

Chipping the wood chips,

Boiling down the water,

Making it.

It took days and days and days.

Myself and four other novices were making the dye and boil it down to kind of a syrupy texture.

And the dye robe made from jackfruit heartwood had a very sweet smell.

And we also made wooden tooth woods,

Like toothbrushes,

Made out of wood.

And so yeah,

We're sewing robes,

Making tooth woods and boiling the,

Making the dye.

Ajahn Siripanyo was my mentor,

Teaching me the chanting.

And Ajahn Jayasaro had gone over to ask Lumpur Liam.

Lumpur Liam had been recently made a preceptor.

I was his second Western monk that he ordained.

The first one was Ajahn Sukhito.

And Ajahn Jayasaro went.

In those days,

Lumpur Liam was,

He was an enigma.

He was a very,

He's very different to how he is now.

He was so everybody,

Nobody doubted that he was pure and equanimous,

But he was like so pure and so equanimous.

It's like you could be sitting in front of Lumpur Liam and ask him a question and he would look at the ceiling,

Look out the window,

Look at his fingernails and not answer and not make any eye contact.

And whatever discomfort or awkwardness you might feel about being ignored,

That's your problem.

He's abiding in emptiness and he hasn't yet felt it appropriate to respond.

So Ajahn Jayasaro is a busy man.

He's got lots of things on.

He's come over.

I've got these five novices.

I wonder when would be the date?

He ignores him,

Gives him no answer.

Ajahn Jayasaro comes back.

We're kind of like,

When are you ordaining?

When are you ordaining?

Ajahn Jayasaro was like,

I don't know.

He hasn't,

He didn't tell me.

And so we,

Some of the monks wanted to,

Wanted some relatives to come from Bangkok and Chonburi,

The Thai monks,

And they didn't know what day.

So anyway,

It turned out that Ajahn Jayasaro sent his secretary and a few days later Lumpur Liam said on the 13th of July in the afternoon,

He said he will ordain us at four in the morning the next day.

So the relatives had to get in the car and start driving to attend the ceremony.

So we were still practicing the chanting.

My practicing wasn't perfect.

Ajahn Siripanyo has a real gift for languages and he was very kind in sharing his gift and trying to help us.

He was making sure our long vowels were long,

Our short vowels were short,

Our double consonants were double,

Our aspirated consonants were aspirated and I was getting things wrong.

But it was like nine o'clock at night and I said,

Ajahn Siripanyo,

I feel like I've practiced enough and I feel like what I really need to do now is go and meditate and go and sleep.

And Ajahn Siripanyo says,

But this is your bhikkhu ordination and the chanting isn't right yet.

I said,

It's good enough.

I have to get the feeling right too.

I have to get the heart right.

I've got the feeling right.

And he's like,

All right then.

Totally unconvinced.

And so anyway,

The next morning we're up at three,

Practice the chanting one more time,

Go over to Wat Phopphong at four in the morning in the dead of night.

And the ordination hall at Wat Phopphong has this big black Buddha statue.

It's about three meters tall and he has these two hands up like this.

It's a particular mudra from the time when the Buddha was trying to stop the war.

It was like forbidding something.

And I was there,

I wasn't feeling particularly confident and I was exhausted because I guess we'd had two weeks of like not enough sleep and too much caffeine and not enough meditation.

And I was already feeling anxious.

And it just seemed to me like this big Buddha was saying,

Don't even think about it.

Stop right there.

No,

It wasn't like some nice gold leafed,

You know,

Painted face,

Sweet smiling,

Bless the universe Buddha.

It was a just stop Buddha.

Four in the morning.

Oh,

And so we're going through the ordination ceremony.

Ajahn Jayasaro was my chanting acharya.

Lompolyam was my preceptor.

And Lompolyam,

He just doesn't,

In those days he didn't bother looking at you and smiling,

Trying to reassure you.

He was like looking at the ceiling,

Looking out the window.

And I was,

I was standing there at four in the morning and I was thinking,

Should I feel heard or offended that I don't have a single friend or a single family member from my past life here on this,

What might be the most important day of my life?

He didn't give us any warning to invite anybody.

Because a lot of,

Oftentimes,

Ordination ceremonies,

They make a big deal out of it.

It's like offering special clothes and yeah.

But I had enough mindfulness and enough humility to realize you're the one that has come to the middle of Northeast Thailand.

You're the one that's standing in this forest,

Dark forest,

In this dark hall at four in the morning,

Doing this strange thing.

Why would you expect anyone else to be here,

Achalo?

This is your,

This is what you're doing.

It's not what they're doing.

And then I looked around and I said,

Well,

These are my new brothers,

You know,

And Ajahn Jayasaro and Lompolyam.

These are my,

These are my family.

These are my fathers.

This is it.

It could have been worse.

I thought,

Okay,

My new family is the virtuous companions.

And so my voice was kind of breathy and scared.

And so they,

They,

I got one of the questions wrong when they asked me,

Do you have leprosy?

I said,

Yes,

I do.

And then the whole gathering laughed and said,

No,

No,

Nati Banteay,

I don't have leprosy.

And that made my face turn beetroot red.

And anyway,

There's a monk next to me,

Ajahn Metiko from Malaysia.

I don't know where he got his confidence or his energy from,

Because he was just like,

I'm a Banteay,

I'm a Banteay,

Nati Banteay,

Nati Banteay.

I was looking and I was like,

Where do you get that from at four in the morning?

What planet do you come from?

And that's the thing,

Like,

We really do come from different planets.

You know,

People have their own karmas,

Their own characters,

Their own kilesas,

Their own barami,

Quite different depending on the past thousand lives that we had,

You know.

And so I did,

I did become a bhikkhu and Ajahn Jayasaro was my karmawajah Ajahn and was my preceptor.

And I had,

Did my first panca at Wat Bananachat.

And so probably the ratio of days that I wanted to disrobe became,

It was probably like two good days and five difficult days.

And the novice period was one good day a week.

The bhikkhu period was two good days a week.

And Wat Bananachat's forest is dark,

Or it was.

Ajahn Sudanto the following year suggested,

Made a suggestion and they cleaned out a lot of the lower,

Lower vines and a lot of the smaller trees made it more airy because monsoon forests in the wet season,

They just get this really,

Really heavy,

Dark canopy and kind of mist sits under them.

It doesn't move.

And many monks would get these strange kind of fevers from probably mosquito borne.

It's probably something that we don't even know what it is.

Don't have a name for it yet.

But these are weird tropical viruses that people get from damp forests.

And so it got cleared out later,

But in the middle of the wet season at Wat Bananachat in the old days,

You couldn't see the Kuti next year.

It was just dark and damp.

Hardly any light got through and the air didn't move.

But keep in mind that it was also a charnel ground.

The reason that the trees were still there was because it was a place where the Thais had been burning corpses for centuries.

The corpses that they burned,

Burning corpses,

But also dropping the bodies,

Burying the bodies of inauspicious deaths.

So if someone had a certain inauspicious death,

It was the custom to just dump them in the forest.

Part of the reason they did that,

Horrible as it sounds,

Was they didn't want the ghost of that person.

An inauspicious death often causes a ghost and they didn't want the ghost to come back to their home.

The Thais are terrified of ghosts,

More so then than they are now,

But they still are.

So they just drop the body in the forest.

So it was also haunted.

And that brings a certain vibration,

The archetypal charnel ground,

The haunted charnel ground.

And it's full of idealistic,

Fault-finding,

Critical,

Competitive Western monks.

And it's the middle of the wet season.

It's dark,

You know,

And I'm like thinking,

Oh my God,

I used to be able to jump on my bicycle and ride to the beach.

I used to be able to go to a movie on Half Price Tuesdays.

People used to hug me when they saw me and say,

Hi babe.

And here I am,

Sleeping on a hard floor in this dark moldy.

You would wash your clothes and hang them up in the kuti dry.

And a few days later,

They have this furry mold on them.

Just,

You haven't even touched human skin yet,

But it was so damp that mold grew on everything.

The floor,

The walls,

The ceiling,

Your clothes,

You.

You have to get like anti-fungal cream when funguses grew on you.

It's disgusting.

So this is the reason why I was like,

I don't know if I can do this.

I want to,

I want to leave.

I want to go back to the sunshine and the comfortable bed and the friends that gave me hugs and the nice smells.

But there were two days a week where the mind felt light,

The body felt light.

There was just this resilient well-being.

Everything was just okay.

So I could see,

Okay,

This is working.

This is working.

As difficult,

It might not be working as fast as I want it to,

But it is working.

So I could see that.

It's the,

It was a tradition for the monks from Wat Nanatat to go into a,

One of the things Ajahn Pasner had done on one of his retreats was going on Tudung.

He had found a tin mine near the border of Burma.

And there was an area of forest that people had a license to mine,

But they decided not to because they just thought it was so beautiful.

It was like a plateau between mountains that had a flowing crystal clear stream,

Had a flat area near the stream,

Very,

Very tall trees,

And there's really ancient bamboo.

And they showed this plateau to Lompopassano and invited him to stay there.

And he stayed there.

He found it beneficial.

And then he asked them if they would mind if he brought the community back,

Particularly in the months of March and April,

Where it's extremely hot in Ubon.

So it became the kind of a custom for the monks at Wat Nanatat to go into this jungle area for two months a year during the hot season.

So I had done that as a novice.

I'd been a novice for four days when we went into this jungle and I was not ready,

But I was there.

So when we went into this jungle,

There were tigers,

Elephants,

Bears,

Pythons,

Cobras,

Centipedes,

Scorpions,

Malaria,

All the good stuff.

And we had to spend 23 hours alone in this dark forest.

And because I had done many meditation retreats before this,

About 10 I think,

One of them was one month long,

Mahasi style.

But I had never had that much time alone.

And probably the mistake I made,

Because I didn't know yet,

Was that I should have made myself a schedule.

I should have given myself a time when I was going to walk,

A time I was going to chant,

A time I was going to study.

I should have given myself a structure,

But I didn't.

And what happened was spending 23 hours alone,

Working with that fear,

Being so exposed of that darkness,

Not having close friends,

The mind kind of collapsed and it wasn't in a good space.

So I remember for the first two weeks,

I really,

I was really scared of tigers.

And after two weeks,

I was like,

Oh tiger,

Please come and eat me.

You know,

That's when I knew that things were going south,

That I didn't want to,

I didn't want to meet a tiger so that I could get my samadhi together.

I wanted to meet a tiger so he could just help me end it.

And I was thinking,

If I,

If I die in the robes,

At least I died in the robes.

And there was a,

There was a,

You know,

There was all sorts of conflicts in Burma among the different,

Different ethnic groups there.

So it was rumored that there were landmines on the,

On the other,

On the other side of the border.

There was no barbed wire or fence or anything.

It was just a line in the forest,

We're in the jungle.

And so the thoughts,

The thoughts did come,

I'm just going to wander off into Burma and find myself a landmine,

Because that's how oppressive I experienced my own mind.

It was not easy to spend 23 hours a day with yourself in the jungle,

Not easy.

The reason I mention it is,

I didn't give up.

After I went to,

Didn't want to go again the next year,

That's when I was in Amaruwati,

Benefited enormously from my closeness with Ajahn Sumedho.

But when I came back and I'd spent panchrit at Wat Nanachat,

I actually decided to go into Dadam one month earlier,

Along with Ajahn Sudanto.

And I did,

I did,

I'd had that insight.

You need to set yourself a study plan and which chants to learn,

Which chants to chant,

When to walk,

When to sit,

Which books to read,

All of that.

And,

But I had,

And before this,

I made a,

I made an aspirational prayer at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha.

I'll probably just talk for about 10 more minutes,

And then there might be a part two,

If you're interested.

So I went to the Temple of the Emerald Buddha because I had this ratio of two days a week where I'm feeling well-being,

And five days a week where it's still really hard.

And I was thinking,

I,

My teachers had been very good teachers,

And they'd been very kind and patient with me.

But I,

I kind of was still rich with suffering,

And that wasn't their fault.

That's a part of my karma,

And this being,

And my sensitivity.

And,

But I did feel that if there is some kind of a metta master that could blast me with their metta every day,

That would be helpful,

That I needed a bit more help.

And I'd heard,

I'd heard about monks with great abilities,

And that's one of the things that the junior monks at Wat Nanachat,

It's,

It's like,

We're playing in this team.

This is our sports.

We,

We need heroes.

So we tend to have these discussions back in those days.

Who's an arahant?

Who's a sakadagami?

Who's an anagami?

Who,

Who's a srimantra?

Who's got jhanas?

Which jhanas they have?

What psychic powers they have?

Like,

That was one of the things the western monks talked about,

Was like,

Which is probably very conceited and presumptive.

We shouldn't be doing it,

But we did,

You know,

Because everyone needs a hero.

So I went to,

At my friend Ajahn Punyo's suggestion,

On the way to the jungle,

I went to the Emerald Buddha,

Because he had told me that that was the place where the devas listened to prayers associated with Buddha's practice.

And so I made that aspiration.

I said,

I'm interested to be a monk for all of my life,

But I'm going to need more help than this.

If there is a master who can help me,

May I meet him?

And so then we went off to the jungle.

Before we went to the jungle,

Actually the next day,

And just to let you know,

The reason I want to talk about this is most people meet the 50 year old Ajahn Achalo,

Who's kind of relaxed and friendly and cheerful.

And you might not know how sincere I've been,

How austere I've been,

How tough I've been,

What I put up with that established this warm,

Fluffy happiness.

So it's,

It's nice to share a little bit of details.

So on the day before going back into the jungle,

Again,

This time for three months,

We went to the police morgue at the police station in Bangkok,

Because we wanted to do corpse contemplation.

So why would we want to do corpse contemplation?

Because we studied that many of the great masters got great results by contemplating the natures of the body,

And the Buddha recommended that monks going to the charnel ground.

So one of the things that was possible in Thailand in those days was for a monk to come in and into the hospital,

Ask for permission to contemplate the corpses silently.

So,

But I don't know if that was the best first choice,

Because the police morgue in a big city like Bangkok,

The police morgue has the suspicious deaths that need to be investigated,

And it has the accidents that happened in the vicinity,

And it has the deaths of the prisoners also go there to have an autopsy.

So we walk in and no air conditioning in those days.

I'm sure it's changed.

No air conditioning,

No screens.

And so if a body's been rescued from a canal and is bloated and half rotten,

That's what it smells like.

And,

And then there's like,

There's a couple of autopsies going like in tandem,

Because they just got to investigate these bodies.

And so,

So I was watching,

He literally took a saw that you would get at a hardware store,

Or first of all the scalpel,

Cut the skin from ear to ear,

Peel the face down over the front,

Peel the back of the head over the back,

Take up the saw from the hardware and just start chopping off the skull,

Chop off the skull,

Crack it off like a nut,

You know,

And then,

And then pull the brain out.

When he investigates the brain,

He put it between the feet,

So it was kind of out of the way.

There's this brain between his feet and then cut the,

From the bottom of the neck all the way to the groin,

Cut out a V shape in the chest,

Took out the heart,

Took out the lungs,

Just kind of place it along the side doing these tests because they have to investigate.

They know,

Forensic scientists know from the texture,

The color,

The smell of these things.

Did the person drown?

Was this person poisoned?

Was this,

Was this person killed before they were put in water?

All those things,

They know these things.

So,

And then take out the liver,

Take out the kidneys,

And then they put it all back in,

Including the brain in the,

That and stitch it up,

And then they put cloth inside the head and put the skull back on and pull up the face and stitch it up.

And,

And so,

Um,

Anyway,

In terms of a body contemplation,

It was,

It was successful.

It,

We definitely got to contemplate bodies,

But it was also a bit much,

Like,

Like all of the blood drains from your face and you get this cold sweat and you feel like you're going to faint and you just,

All you can say is don't faint,

Don't faint,

Don't faint.

And then you,

The smell,

When they cut open a human body,

It's like a thousand bad farts all at once.

Excuse my French.

That's,

That's what it's like,

Right?

Because that's what intestines smell like.

And so the compulsion,

You just want to throw up.

You want to get away from it visually,

Energetically,