Breath As A Refuge For The Digital Age With Jacques Rutzky

In this fourth episode of the anapanasati series, I welcome meditation teacher Jacques Rutzky for a deep, personal conversation on mindfulness of breathing (anapanasati) and its role in daily life. Jacques shares his 50+ year journey into meditation—starting at age 16 in Detroit, discovering the Pali Canon, a pivotal 1974 retreat with Joseph Goldstein, and 45 years under Thai teacher Dhiravamsa (formerly Phra Bhikkhu Dhammasuddhi). He emphasizes practical, individualized breath practice over rigid methods, adapting to where students naturally feel the breath (nose, chest, abdomen). The discussion explores modern challenges like screen addiction and fragmented attention, hindrances (craving, aversion, etc.), and using breath as both anchor and refuge. Jacques advocates experimentation, slowing down, and viewing the mind as one tool among many—not the only one.

Transcript

Holness.

Welcome.

This is Josh of Integrating Presence,

Interskilled2,

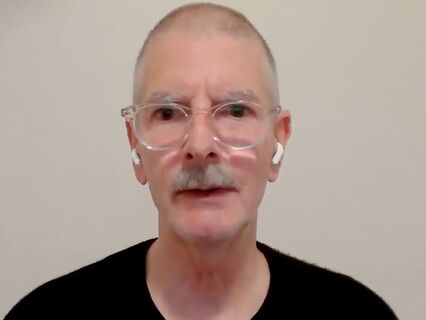

And today I have Jacques Ruski with me.

Jacques,

What's going on?

Not much.

I try to live as simple life as possible,

But today is a good day.

I had a good night's sleep.

Oh,

Lovely.

All right.

I will give you the standard question here.

Who is Jacques and what kind of work does he do?

That's an interesting question.

Who is Jacques from a Buddhist point of view?

If we accept or eventually see,

Have the experience of seeing the arising and passing away of the self,

Then the sense of identity dissolves.

And so,

Jacques is just the name.

But to answer your question more commonly,

I would say that currently,

I live in Evanston,

Illinois.

I teach meditation.

Many of my students are from Oberlin College or were from Oberlin College.

I lived there for about 15 years teaching the students.

And prior to that,

Lived in Woodside,

California.

And prior to having a dramatic illness,

Viral encephalitis,

I was a psychotherapist for 20 years in California,

In the San Francisco Bay Area.

And I would consider,

Most people would consider me retired,

But for me,

Teaching is semi-full-time.

And I really enjoy the connection with people who are very interested in meditation,

Anywhere from a beginner to someone who's been sitting for 25 or 30 years.

And I like being challenged.

Well,

Great.

So do I.

And I like asking a lot of questions.

That's why I have a podcast too,

Right?

But I really,

I can sense the depth of your practice.

I'm so great.

I reached out to you.

I just tell the listeners here how I found you.

I practice with some of your maybe current and ex-student,

And I won't say the names,

But I really impressed with both of them,

Of course.

And so when they listed you as one of their teachers and I hadn't seen or heard your name before,

I thought,

Well,

This is interesting.

I got to go find Jacques here.

And I looked online and I didn't see any audio interviews or video.

And I,

Well,

Here's a goldmine.

I've struck the gold in a certain sense,

Right?

Or maybe I just didn't do my web search well enough or something like that.

No,

You did.

You did.

I did.

Okay.

Well,

Great.

I'm so glad I reached out then.

I have no ambition to acquire a large following and don't write books on meditation.

There are enough books written about meditation.

I'd rather have personal contact with people.

One of the difficulties these days when you have a teacher is that that teacher has hundreds of students.

And even if you go on retreat,

It's unlikely that you'll actually have an interview with the teacher.

You'll have interviews with their students.

And I'd much rather have a deeper connection with people.

And so I see fewer students.

And it's nice to watch the development of a deeper state of the practice over time.

It is a really good point here.

I mean,

I see the pros and cons of each.

On one hand,

We can bring more people to the Dhamma that way.

But like you said,

There's something to be said about putting this me bag in front of another me bag.

Well,

Hopefully it's a meat suit instead of a me bag.

That's kind of when we get into unhelpful selfing.

That's a Ajahn Suchito term that I really love.

It's just kind of humorous too of how the selfing that you talked about at the beginning can be.

But yeah,

There's something to be said about it.

And these experiences,

I think,

Are becoming more rare and at the same time more cherished.

And hopefully we don't romanticize it too much because we do hear some spiritual stories where people go off in the Himalayas and try to seek a guru that doesn't have any kind.

I think those are really heartwarming and uplifting stories.

So there's something to be said about that.

So yeah,

I feel there's pros and cons to both of these approaches.

And I'll just say,

The teacher I'm working with now is kind of on the same vein.

You have to be a really dedicated practitioner to work with him.

And we still haven't got to meet in real life just due to a lot of different,

I would say,

Challenges,

But the time seems like it could be coming.

So I love this model too of having,

For many years,

I didn't have a core teacher in my practice.

I was kind of wary and,

Oh,

I can just do it from books and dhamma talks and my own.

But there is really something to be said about one-to-one access with a teacher,

Especially if one resonates,

Right?

So finding that match of someone we really respect and admire.

But not only that,

That we're actually seeing benefits in our own lives and then that's kind of rubbing off with others too.

Maybe I'm being a little bit hypocritical too,

Because I have a podcast here.

I talk to a lot of people from all walks of life and it does get a little bit of bigger reach,

But not like some of the huge ones either.

So I would say there's a time and a place and pros and cons for all these approaches.

But I just wanted to acknowledge that and give that validation because I find that really very helpful in my own experience when at one time I didn't really see it or value it as much.

So I just want to throw that out there too.

Yeah,

Of course.

And I started out at the age of 16 observing my family and especially my parents and noticing how unhappy they were.

And I didn't want to end up that way.

And so not having any teacher available in outside of Detroit,

Michigan,

I found a spiritual bookstore and sort of browsed every possible option that was available until I came across the Pali Canon and started reading.

And my first book of meditation was helpful.

And I think due to my own lethargy and lack of understanding,

Mostly I would fall asleep.

But I kept at it with finding the Satipatthana Sutta as the main book that I would read from and gain understanding from and kept meditating.

And when I went to Oberlin College,

Turns out that my roommate was also a meditator.

And a year later,

I was making preparations to leave for Thailand to become a monk.

This was after doing my first retreat with Joseph Goldstein.

And what year was this?

1974.

Wow.

So you came to the Dhamma early.

And yeah,

I would just do a brief background.

I wish I would have had kind of more wholesome,

Skillful introduction.

But like many of us,

We come through the Dukkha door,

I think,

To practice.

For me,

It was the beats.

And I found out later why it was exciting,

Kind of thrilling,

And they did have some knowledge of Dhamma.

That's maybe not the most wholesome,

Skillful way that I would have liked to,

But it was better than nothing.

I looked around.

I saw the Four Noble Truths.

I said,

Oh,

It hit me real hard suffering.

Oh,

Yeah,

That's what's going on.

I could see it.

But then the Second Noble Truth,

Okay,

I don't understand that.

Third Noble Truth,

Oh,

That's great.

But Fourth Noble Truth,

Oh,

This is,

I don't understand any of that.

This is completely over my head.

So I was completely overwhelmed by that First Noble Truth.

I could see,

Yeah,

There's no doubt.

But for what,

No wisdom,

No kind of sila whatsoever,

Unfortunately.

So then it kind of hit like a ton of bricks years later.

But use that to the advantage of an opportunity for coming to the Dhamma.

So in that sense,

It's not all that bad.

And it sounds like you've had some challenges in your life too.

So you're no stranger to the Dukkha door either.

But I think it's quite amazing that you had the good fortune and probably maybe past parami to get in when you did.

And so before we get into Anapana,

Where I want to focus more,

Continue though,

With your journey too about maybe real briefly,

If you want to say how you met Joseph Goldstein,

Maybe how you got involved in whatever we want to say about the California Dhamma scene.

But I'm also interested in Thailand because I'm booked on to do winter retreat at Chithurst in Thai forest tradition of Ajahn Chah in England in February and March.

So yeah,

I'm familiar with this tradition and very inspired by them too.

And then of course,

The Satipatthana,

It's foundational,

Right?

So yeah,

Before we get into Anapana,

Which I want to say a little bit more about.

Yeah,

Just because I'm kind of a newer generation to this.

I didn't live it.

And I'd like to kind of know from more,

Not the huge Dhamma superstars,

So to speak,

For lack of better term,

Kind of how that time period was and what it was like too.

Well,

At that time,

My roommate from Oberlin,

I had gone out west to study at a martial arts academy in Colorado thinking,

Oh,

That's the thing that I'm going to dedicate my life to in Tai Chi.

And I followed that teacher out to California.

And then my roommate sent me a message.

This was a letter because they didn't have email back then talking about this retreat in California.

And I just worked as much as I could to save up money for the retreat.

This was 30 days in the Sequoia National Forest,

Silent retreat,

My first retreat.

And we started out sitting an hour for each set.

And it was so clear after that retreat that this was how I wanted to continue.

But I was still looking for a teacher that I felt a deep connection to.

And so I was preparing to go to Thailand and just wander and search for a teacher.

And got a flyer in the mail that said,

Well,

There's this Thai monk who's coming from England to give a retreat on the East Coast.

So I wrote them a letter and said,

If I help with the cooking and run the kitchen because I cooked at Oberlin,

Can I do the retreat for free?

And they said,

Of course.

And so I hitchhiked across the country in the middle of winter.

Literally,

I started out on December 31st.

And when I hit the Rockies,

There was an enormous snowstorm.

And I remember arriving in New Haven,

Connecticut,

And meeting the manager of the retreat,

Who was so kind and welcoming.

And then a few days later,

We went to New York,

Because my teacher was giving a talk at Chogyam Trungpa's New York Center.

And I remember we were sitting up in the balcony,

And I had never had contact with him.

I was still wondering what was going to happen.

And the doors open,

And he takes two steps forward.

And the room is filled with people from Trungpa's group.

And they're all talking and chatting away.

And my teacher just stands there still.

And then gradually,

People in the room start noticing that the guest speaker has entered the room.

And so it was like the Red Sea parting.

And he walked very slowly,

Very self-contained,

Very mindfully.

And I just had this feeling just in my chest,

Tears started coming down my eye.

And a phrase came in my mind of,

I'm whole.

So we had a little bit of contact throughout the first retreat.

It was 30 days on the East Coast.

At the end,

He asked me if I would come to England to be the cook at his retreat center in the south of England.

He liked my cooking.

And I would notice very intently when he would go back for a second,

And what he would take for a second.

And then I would know,

Ah,

He likes that.

So I was cooking for him most of the time.

And he was my teacher for 45 years until he died.

And I tried as much as possible to go to,

Let's see,

For the first eight years,

I was his cook.

And then I became a therapist and would try and go on retreat once or twice a year,

Wherever he was.

And it was a rare and wonderful relationship.

And there were these odd little things that made it special.

Um,

For example,

If I at the tail end of the retreat,

The last day,

He would say to me,

Jacques,

I think this would be a good retreat for you to go to.

And he would hand me a piece of paper with an address and a telephone number.

It could be in Great Britain,

It could be in Germany,

It could be in France,

It could be somewhere in the United States.

And we would have zero contact for a year.

And I would just show up in Grenoble,

France,

At such and such an address.

And I would knock on the door and he would open it.

And I'm sorry,

Go ahead.

No,

This is great.

So I got me in a little bit of an interesting position here.

Because if you've mentioned it,

I missed it.

And I'm sure you're okay with sharing the name of the teacher,

Especially since it's past now.

Yeah,

Please,

Please do because I'm in suspense here.

When he was a monk,

His name was Prasobhanadamasuddhi.

And after he did the seven year sort of PhD in Buddhism program at Mahachula Longhorn University in Bangkok,

He was interested in meditation.

And as he told me,

No one in the university encouraged him to go into meditation.

And so when he graduated,

He wandered in the forest and found a teacher and stayed with that teacher for two years.

And then went back to the monastery where he was staying at.

And eventually,

His,

The abbot of that monastery invited him to England.

And because there was a Thai temple in London.

And,

And then he realized that those who were interested in meditation were not the Thai people who he was serving,

But all the Westerner.

And so he,

He found that when he wore a robe,

And sat on a golden throne at the temple,

There was a great personal distance between him and the student.

And so he took off the robes and just kept on teaching meditation for the rest of his life.

I see lovely.

Oh,

Excuse me,

Please,

Please,

Please go through.

And so when he took off the robes,

He took another name,

Which he is mostly known for,

Dhirubhamsa.

Dhirubhamsa.

V.

R.

Dhirubhamsa.

Vichitthalatnat Dhirubhamsa.

Dhirubhamsa.

Okay.

So for me too,

And some of the listeners that don't know kind of this distinction of Thai Buddhism,

Do you feel it might be helpful to give a little bit of a classification about that to kind of know where he fits in with lineages too?

Or do you think that's important?

Or what should be said about that?

That's a good question.

Buddhism in Thailand is Theravada Buddhism.

And it basically means those who follow or take the Pali Canon as the writings that were the words of the Buddha.

That is sort of like an assumption,

Although who knows what's happened in 2,

500 years,

Especially since the first 300 years after the Buddha died,

Everything was a verbal transmission.

Now,

One of the things that I found very interesting about my teacher was that he was very open to learning about his students and about the culture where he taught.

And so when we were on retreat for a month,

He would give a talk every other day after the sit after lunch.

He would include the basics of Theravada Buddhism in a 30-day retreat.

But mostly it was his way of understanding the Western mind that allowed him to use language where they could understand what was in the basics of Theravada Buddhism and especially the Satipatthana Sutta.

At that time in his life,

He was very adamant that mindfulness was everything and forget about concentration.

That's a waste of time.

And later on in life,

He started experimenting with the jhanas.

I see.

I guess where I was going with that,

And there's a few other things to throw in here,

Is in Thailand,

I've heard there's a more scholarly direction and then the other one,

And one's more common than the other.

Help me with the names here.

And then let me throw in a few more really brief things.

What year did you go across to the East Coast?

And also the first one in the forest,

Who was the teacher?

And just to help me clarify,

Who was the teacher in that retreat as well?

And then one really quick one,

Why Thailand?

How did you first get your mindset that you wanted to go to Thailand,

Even though it didn't pan out exactly like that?

There's a few things there.

Because Joseph talked about Thailand and how.

.

.

Ajahn Chah,

Right?

He was.

.

.

Yes.

He had a very meaningful time with Ajahn Chah.

And oftentimes,

In any kind of religion,

There is a split between those who follow the word and are very academically oriented and those who are very oriented towards experiencing the practice itself.

Excuse me for a second.

Sure.

And help me remember this.

Is it Dhamma-yut?

Or help me,

The classifications,

The terms.

Do you know these in Thailand?

Is it something-yut?

My memory is not as good as it used to be.

Okay.

But I also tend to leave out things that are not so important to me.

It's a good point.

Exactly.

So those in the.

.

.

And if you're familiar with Thai Buddhism will kind of know what I'm alluding to here,

But I'm forgetting too.

And it's really not that important to have such a classification.

Well,

The Thai forest tradition,

As far as I know,

Honors and follows the more ascetic practices that the Buddha allowed.

And my teacher was not of that orientation.

I think he was very good at picking up on who he was teaching to.

And so the ones who were more interested in a more difficult path might end up in Thailand themselves.

I see.

Yes.

From what I'm remembering,

Ajahn Chah,

He started off in a more scholarly lineage and maybe around when he met Ajahn Mun,

And then got into more of the forest tradition.

And I can't remember the exact terminology,

But it's clear when we talk about Dharma practice and study,

There seems to be these general rough classifications of scholarly types,

And then more practice-oriented types.

And you get a rare combination where you have some who do or excel in both.

And I would add another one more faith-based,

And this is a common,

I think,

Throughout different types of religion too.

And so,

Yeah,

I tend to side more with the practice,

Although I love going deep diving into Pali Canon too.

And it reminded me of a thing from the Canon too about,

I forget exactly what the reference is,

Where the teaching is you pay attention to the king,

The king's cook,

Right?

And how you're paying it,

What does he like?

What does he not like?

And yeah,

You'll do a lot more successful if you notice what they like and what they don't like,

And then cater to that.

I don't know if I'm phrasing that in the most helpful way,

But I couldn't help but be reminded of that teaching.

Maybe you could elaborate or clarify that a little bit if you'd like,

But I do want to move us on here to Anapana.

And I guess maybe a jumping in point since you mentioned Satipatthana,

Which is,

Some people say,

Four foundations of mindfulness.

I like four frames of reference,

Kind of the four establishments of mindfulness too.

So there's a little bit of playing with the words,

But basically on the topics of the body,

And there's like a six-fold way to pay attention to the body or be mindful of the body,

Then into Vedana,

Pleasant,

Unpleasant,

Neither.

And then Citta,

Heart,

Mind,

And then Dhammas,

Which is a whole list of lists.

And so it can be,

Yeah.

So there's a lot to it in a way,

But the reason I bring this up is because if I'm remembering somewhere else,

It says those who excel at Anapanasati fulfill the four foundations of mindfulness.

And I don't know if it's vice versa or not,

But the commonality we have through both of these in Anapanasati for anybody that doesn't know is often translated as mindfulness of breathing.

So the very first one deals with in and out breath,

According to a lot of different translations,

And dealing with the bodily formations or the bodily formation.

And there's similarities in the Satipatthana about where it starts off with the breath too.

So that's the common jumping in point,

And I would say thread that runs throughout both of them as they progress or things.

So anyway,

I want to see how you just kind of approach that in general as maybe a starting end point,

And then want to get into just as very practical,

How you teach students Anapana and maybe what kind of flavors you add that you don't see in other teachers or maybe wherever you want to take it and how you want to jump into this,

I think.

One of the things that I really value about mindfulness of the breath,

One of the many,

Is that it's always there.

So we don't have to create an image or a thought or an idea.

The breath is,

For the most part,

Obvious because we breathe in and we breathe out.

Then what comes to my mind when I'm talking with a student is,

Where do you notice the breath?

And some people notice it in the abdomen,

Some people notice it in the chest,

Some people notice it in their sinuses,

And some in the tip of the nose.

And when I began teaching,

I was a bit rigid in following what my teacher taught as well as what was in the text.

And when people had difficulty,

I would interpret that as,

Well,

They didn't have enough concentration,

They were impatient,

Their need for stimulation was higher than one might get if you're just sitting still and noticing the breath.

And over time,

I came to realize that the fault was not in the student but in me.

And I began to ask my students,

Well,

Where do you notice the breath?

And they would tell me.

I said,

Well,

If you notice it there the most and it's obvious,

Stay with that and let's see what happens.

So,

It all became like an experiment between the two of us trying to find what worked.

And so,

Mindfulness of the breath is both a concentrative technique because we're focusing the mind away from extraneous circumstances,

Sounds,

Sensations,

And we're coming just to the breath.

And so,

That develops concentration and the mind begins to calm down.

And then it's easier to see what arises,

Whether it's in the body,

In feelings,

In consciousness,

Or mental objects.

And for most people,

Staying with the breath can be the main challenge of the practice for years.

I've had a few students after a period of time,

Five or ten years,

Say,

Um,

Why didn't you tell me it was going to take this long for me to be able to stay with the breath for maybe half a sitting?

And I said,

Well,

I didn't want to discourage you.

So,

I just respond to what they ask about.

And I find that the breath,

As you said,

Is not just the beginning of the practice.

And then,

As stated in the Satipatthana Sutta,

Then there is,

Um,

I always forget these words.

It's mindfulness of the body moving.

Um,

Clear comprehension.

Sampajanya,

Right?

Sati Sampajanya?

Yes.

Basically,

Being aware of wherever you are and whatever you're doing.

And then,

Uh,

The practice continues to pay more attention to what's going on inside,

Um,

As the mind becomes more settled and aware.

And,

Um,

Let's see,

Going back a little bit.

Um,

So,

I find that the breath can be both,

Um,

An anchor in the sense of concentration,

Um,

But also a refuge.

When things become overwhelming and there's too much going on,

Especially inside the mind,

Going back to the breath can become a refuge from all of that chaos until the mind calms down.

And then we can notice what is going on because we're not reacting so much.

And in our culture these days,

Um,

Most of the students who come to me have been trained on screen and are so used to so much stimulation.

I remember one student,

Uh,

Asked,

Um,

Told me about how much he was addicted to his telephone.

And I,

I was curious.

I,

I asked him,

I said,

How much time do you spend on your telephone?

And he said,

Oh,

I can find out.

And so he got the telephone and punched a few buttons and he said,

Yesterday I spent six hours on my telephone.

And very few,

Little of that time was spent talking to someone.

It was looking,

Looking at images.

Yeah.

Now this is,

Um,

So yes,

I would say,

Okay,

So I'm of the generation that's kind of between the generation you're talking about,

Imagine,

And your generation.

So I know a little bit of both of these ways of life.

You know,

It's the last generation to know a world before internet,

You know?

And so it's,

Um,

It's tell people when I was in the library,

People were making fun of me,

Oh,

This internet,

It will never take off.

Now we see it inseparable basically from everyday life.

I mean,

I think even certain religious communities like the Amish or something,

They,

They're not totally removed.

You know,

They still interact with people that are,

You know,

Still using it.

So I think this is one of the modern day challenges when it comes to meditation.

And I want to ask you some other,

Like,

What else do you see when it comes to meditation?

But I think this is the biggest one.

And I'm curious now,

How do you work?

And also for myself,

I've noticed in my own experience,

When I'm like talking like this,

I can have more opportunity and space to be mindful.

It's not that big of distraction.

Uh,

But when I'm interacting constantly,

You know,

Either typing or using a screen scrolling or touch pad on my,

So anytime I'm interacting with this machine,

Um,

A lot of times,

Oh,

There's so much.

Okay.

Uh,

One of my teachers said,

It's basically greed that I want to get things done and keep pushing myself.

And I didn't see that.

I mean,

It's completely obvious now,

But I didn't even see that it's just greed that I just wanted to keep getting things done.

Cause I identify with doing and accomplishing yada,

Yada,

But even to the point where I'll,

I feel my body tensing up,

You know,

I feel the mind state that's not really helpful or wholesome and I'll override that to push through to do something,

You know?

So do you even gone through trying to develop some kind of mind,

Uh,

Having some kind of mindful device interaction,

Um,

Other than a complete abstinence.

And I've done that too,

For the first time,

Probably since the nineties,

You know,

I did a whole month in Korea Zen retreat where I handed in my electronics and I,

Oh,

Let me tell you,

I had no idea how much my sense of reality is now,

Uh,

Tethered to devices and interacting with them.

It was,

It was quite an eyeopening experience to,

To really see how,

Um,

Serious this can be,

You know?

So,

Yeah,

I guess practical things,

Um,

Inside and outside of meditation of this and any other challenges you see with students.

And then if there's any link to the breath too,

Because I know the breath can be a really good gauge of just how we are.

Cause it's anapana,

Lamport Suchito talks about how,

Um,

You know,

The Sanskrit is prana.

So it's like the life force energy.

So for me,

It's also a really good gauge when I can be mindful to notice it throughout daily life,

The more constriction there is in the breath,

You know,

It's kind of a gauge of what else is going on,

The more ease and free flow and kind of more energizing on the in-breath and relaxing and releasing on the out-breath.

So in that sense,

But yeah,

What have you come to learn and know about this?

Well,

Um,

Usually that depends on,

Um,

Who I'm talking to.

But if I just address the things that you've brought up,

I might suggest that,

Uh,

Depending on what is most obvious to you,

Um,

For example,

If you're aware of tension in your shoulders,

The more that you're clicking on the keys,

Um,

Take a moment to relax that just a little bit.

Secondly,

Uh,

You might experiment with slowing down how fast you type.

One of the things that we do when we're on retreat is we slow everything down.

And while I wouldn't suggest that you do,

Um,

Work on the computer the way we do walking meditation so slowly,

Um,

Even just a little bit increases mindfulness and awareness of how,

What you're doing affects you.

And then you can begin to naturally,

It will change over time.

Um,

Some people,

Uh,

Set timers every 10 minutes and they take a minute to take a break and just breathe.

Thich Nhat Hanh,

One of his practices every hour was to have a bell rung and people just stopped whatever they were doing and just paid attention to their breathing or just being,

Uh,

We become a culture of doing,

Not of being.

So I would give you permission to experiment,

Um,

Try different things and see what works and what has a beneficial effect and then go from there.

And I,

I have a number of students who,

Uh,

Um,

Work on computers.

Um,

Some just inputting data,

Some are more creative,

Uh,

Making websites.

Um,

Some are involved in AI,

Some are involved in security,

Um,

Have the computer whole system and process.

Each one finds something different that helps them reconnect with being rather than doing.

It is.

And it,

I don't think it's cliche to say,

Yeah,

We are human beings not doing.

That's a,

It's a really good point.

And just to echo the fact we think when you drive in a car,

How much we miss.

And then when we ride on a bicycle,

Kind of how much we miss.

And even when we're walking fast and then even slowing down,

I mean,

I was in the forest in Norway and I could just bend down and look at this little section of the forest.

It's like this huge microclimate and world within itself.

And usually just,

Just walk right by it.

You know,

I could spend,

Um,

You know,

The attention spans lengthen with,

And that's another thing we've,

Uh,

A lot of us,

I feel I could say that,

Uh,

Our attention spans are so fragmented now due to different media and different causes and conditions,

But to just sit and find fascinating and enthrall all the different tiny things that are going on.

It's one little patch of the forest,

You know,

And that can be brought to our breathing and how,

Yeah,

Every breath is,

There's no breath,

You know,

There's similarities,

But each breath is uniquely different.

It's,

We've been,

I think,

Conditioned at least in the West,

As far as I know,

Most of the time to have,

Um,

At least with media that,

You know,

You just think 20 years ago,

They used to show long shots,

Like on movies and TV shows,

But now it's just every,

Even a few times a second and just kind of dis,

Dis,

Uh,

Disoriented and fragmented in our attention and really having a long attention span is,

Is huge.

You know,

One of the things I was trying,

Uh,

Experimenting with too is,

Is sitting in meditation,

You know,

And then,

Then coming out and then grabbing my device and then just paying attention to how long it takes before I lose mindfulness and just have no awareness of,

You know,

Just being completely absorbed into the screen,

You know,

And then realizing,

Okay,

I'd sit that down,

Come back to sitting,

Start over,

And then maybe building a muscle that way.

So that's,

That's one way I have experimented.

Yeah.

And if you found success with it,

Keep doing it.

It's a really good point.

You know,

The Buddha talked about,

He was a pragmatist.

He,

It wasn't all theory and philosophy,

You know,

Skillful means that are in the real world,

Not theory,

Theoretical things.

So yeah,

I will definitely echo that.

Yeah.

Right.

You mentioned,

Uh,

Movies with,

Uh,

That promote a short attention span,

One of my favorite movies,

But one of the things that I found after watching it for like the fourth time was just how long the takes were.

The camera following someone for a long period of time,

Even through doorways and into other rooms and being able to watch how people moved,

A contemporary person closer to our time.

And he was known for his long,

Long takes that had an effect on who chose to watch his movies because some people didn't have such long attention spans.

That's right.

And,

Um,

I think of just why we're on movies,

I think of film where it's all just in one room,

You know,

And I guess it had different angles,

But to be confined in that,

And what's the old saying now I'm free associating here,

Almost that all of,

I forgot who said it,

Basically the problems in the world come down to not being able to sit alone with yourself in a room.

Meditation makes that possible.

And it's,

It's just amazing how much kind of problems dissolve or solve themselves when we're,

When we're able to do that.

And of course,

Uh,

Then I think of a just juxtaposition on this last movie reference here for a while for me,

Um,

Where I think the entire film was shot in one take.

However,

There's a lot of distracting things going on in it.

Cause it's like an action movie and there's,

There's the kind of ridiculous violence and stuff.

But apparently I think it maybe it was an ode to the past where you do these really long takes,

But yeah,

I think I look at some of these,

I put some of these older movies on sometimes.

And I,

Even in myself,

I feel that I've been where I just get more disinterested.

I mean,

I think the pace of life is faster now.

You know,

When I look back in my movie buff days in college and I was able to sit through a lot of old classics,

I think a lot easier than I am today.

So these are really interesting phenomenons,

How we can,

You know,

Do maybe due to Anita things change quite a bit,

But there's also these universal qualities that are still there.

I think that are a timeless,

No matter what area our arena we're in or what the culture we're in.

And of course,

To bring it back to the breath,

The breath,

I feel is one of those.

So no matter whether we like it or not,

As long as we're,

This body is still alive,

There's breath coming in,

Breath going out.

It's just a matter of how tuned in we are and how much we notice of it as well.

Yeah.

And there's a lot that happens in between the end of the in-breath and the beginning of the out-breath.

It's easily said,

But it's not an easy practice.

Even just paying attention to the breath is a challenge.

Well,

I know for me it is too.

And it's been my primary practice for the last couple of years.

And still,

You know,

I've touched into it in the prior years of practice too.

So let's talk about kind of these more practical ones,

Distractions,

Right?

So concentration practice,

If we're using it for Samatha practice of breath,

The effect of it is non-distraction.

So we touched a little bit about real world distractions.

How do you deal with,

I think the common one you talked about a little bit early is kind of the wandering mind.

Now,

I talk to teachers who will say,

You know,

Well,

Thinking isn't the problem,

You know,

It's okay.

But,

And then they go into kind of really vast detail of basically what it amounts to.

It is a problem.

And then I've had teachers that just flat out say,

You know,

Thinking is a hindrance.

And so,

You know,

But there is a place for thinking.

We can't,

We have to have it in our lives certain times,

Right?

And it makes sense for critical thinking skills.

I think a lot have gone away too.

So I don't want to throw the baby out with the bath water at the same time.

It's not the tool for everything.

I think at least in my experience,

I've got kind of validation and praise for,

You know,

Certain types of thinking and mental activity.

We look at some of the workplaces and how people are expected to be engaged with the mind all the time,

You know?

And so like,

What is the right relationship to this?

How do you deal with this?

Maybe when in meditation,

Outside of meditation,

If there's overthinking,

But also just how we can befriend the mind,

But also be stern if we need to be with it or yeah,

Just in general and anything you want to say about this and especially in regards to breath meditation and working with it with breath meditation.

Yeah.

Well,

I see the mind as a tool,

But not the only tool in the toolbox.

And very often we get used to and end up with a favorite tool,

But that tool isn't appropriate for every situation.

But to continue with the metaphor,

The body gets used to holding that particular tool in a certain way.

So when we let go of it,

It feels like something is missing and we yearn for it and we want it back because we want to,

If it's a hammer,

Beat something.

If it's a screwdriver,

We want to turn something.

And I don't take either position to be the only possibility.

Thoughts are a hindrance and bad and we have to get rid of them.

Or one student reminded me of something I said the first session that he came to see me.

He asked me about thoughts and I said,

Well,

Just think of them as like a cloud.

Just let them pass through.

And that allowed him to develop more concentration rather than a clenching very strongly to the object of the sensation of the breath.

For him,

That would have been antithetical to his nature.

And sometimes if we pay attention to thoughts that are racing along,

It only gives them more energy.

And the Buddha even said that anytime something becomes an obsession,

Better to let go of it and turn the mind to something wholesome or neutral.

And then when the mind calms down,

Then if a thought arises,

We can look into it and see what it's about.

Be curious about it.

Be investigative.

Observe it.

Then it ceases to be in control of us and we're just observing it.

And everyone will have success with a different method or a different attitude.

So I think the most important thing is to find what works for you.

Really good points.

So I guess some other things that will come up is hindrances.

So we've kind of framed it maybe,

Maybe not a hindrance,

Right?

So I guess,

How do you work with the hindrances?

Do you deal with those directly?

Or yeah,

How do you approach the hindrances?

On occasion,

When a person is talking to me and it's just so obvious that what is coming up is they're wanting something that doesn't exist or isn't in their grasp.

I might briefly talk about the hindrance.

And each hindrance has an antidote.

Let's see if I can remember all five.

So there's craving,

Wanting,

Desiring something.

There's hatred,

Anger,

Judging,

Criticism.

There is restlessness,

Agitation,

Anxiety.

There is sloth and torpor.

Sloth is a slow mind,

Slow to be able to notice what is being looked at.

And torpor is a dull mind,

Not clear.

And the last one,

What is the last one?

Doubt.

Doubt.

Yes,

Of course.

Doubting the Buddha's teachings,

Doubting one's teacher,

Doubting one's own experience.

And doubt leads to a kind of malaise that can lead to not being interested in practicing.

Because if we have what we call a really good sit,

Quiet,

And then the next sit is full of thoughts,

It's easy to doubt that,

Oh,

You know,

Somebody is responsible for this,

Or the path itself is only for a few,

Not available to me.

And then my teacher used to say,

We all have our pet hindrances.

For sure,

Yeah.

It reminds me of that old Western Dhamma saying that it's nothing like a good sit to ruin the rest of the day.

Meaning that you're trying to get back to the one that it was a good sit,

And oh,

I'd never live up to that again.

Yeah,

Yeah.

I always thought that was a good humorous way to look at it,

Yeah.

Well,

I guess one thing that comes up,

I might as well just ask about the more practical things is practice here.

I've had energetic blockage,

I would say,

In my nose from time to time.

So sometimes it will flow,

And sometimes it will be blocked up,

And it's usually the right side.

And I hear some people will say,

Well,

You know,

Normally,

If you're paying attention,

The one side of the nostrils will block up for a certain amount of time,

Then will open up,

And the other one to kind of give the other one a rest,

Right?

Because I hear yogis say that,

Then other people don't notice it,

Or this doesn't happen to them.

But what I've noticed,

It's usually just the right nostril for me.

And I've had my nose broken twice back in the day with baseballs.

And then when I lay on my left side,

It tends to open up a little bit.

But how do you work with like physical things other than just saying,

Well,

Choose a different meditation object?

Is there still a way to work with the breath?

Or just maybe anything you have to offer around working with that,

I guess?

Well,

Just taking your difficulty as a subject of conversation and connection between us,

You know,

If the right nostril doesn't allow air to flow,

There's no point in frustrating yourself trying to make it flow through that.

So if it does come through the left nostril,

Pay attention to that.

It's easier said than done,

Right?

So the first step is catching that.

And usually,

That's really what it takes,

Because then I can see in my own experience,

Oh,

This is not helpful.

I'm being in conflict,

And there's agitation,

And then there's aversion.

And yeah,

And when we can't see that,

We can't see that,

Then there's really no hope.

That's why mindfulness is so important.

As soon as I can see that and then say,

Wait a second,

What are you doing here,

Josh?

Or,

You know,

This is not helpful.

You're going to be in conflict with that.

You're trying to force something the way you want it,

And it's just not working.

And you're still like ramming your head against the wall.

I mean,

That's kind of like the definition of insanity,

Doing the same thing over and over,

Expecting different results.

So yeah,

The first step is obviously seeing that.

And then the Brahma-Vihara qualities of bringing some compassion to that,

And kindness to that too,

Because yeah.

And then when I remember that,

Sometimes the body will,

And whatever's going on there will relax enough,

And then the air starts flowing around again.

So yeah,

Thank you for that helpful reminder.

I appreciate that.

Yeah.

Well,

Jacques,

I think we've covered some good ground here today.

I appreciate you coming on.

I want to see if there's anything else around the breath you'd like to talk about,

And meditation in general,

Before we start wrapping up here.

And then you can leave with a message of what you'd like to take folks out on today.

Something to go out with is,

I'm always amazed at how practical so much of what the Buddha taught applies 2,

500 years later.

And I especially enjoy listening to his conversations with just one other person.

Something to go out on.

The breath is always there.

If you're not breathing,

You don't have to worry about it.

So the breath is always there to notice.

But if you're driving,

Don't focus on the breath.

Focus on what's in front of you.

If you're walking,

It doesn't mean the breath is the best object for that particular activity.

I find the soles of my feet touching the earth to be good for me.

And be free to experiment.

Find out what works for you.

Well,

Lovely,

Jacques.

Thank you so much for doing this.

I'm so glad I got a chance to meet you and come on and sharing your practical insights and wisdom and just your state of being and presence and what a deep one it is.

And I really appreciate that.

And so may all beings everywhere out there come to cultivate optimal sila samadhi and panya for yourself and for others and for all beings everywhere.

May all beings everywhere realize awakening and be free.

Thank you,

Jacques.

You're welcome.