The One You Feed: A Conversation With Culadasa (Part 1)

I'm thrilled to provide you with this episode of the podcast. As in every episode, we discuss the mind and the words of wise men and eternal ideas that can allow us to live as we should: with happiness and balance.

Transcript

You sit down there to meditate and it becomes really clear that there are different parts to your mind that have different ideas about what you should be doing while you're sitting there.

And some of them don't even think you should be sitting there.

Welcome to the one you feed.

Throughout time,

Great thinkers have recognized the importance of the thoughts we have,

Quotes like garbage in,

Garbage out,

Or you are what you think ring true.

And yet for many of us,

Our thoughts don't strengthen or empower us.

We tend toward negativity,

Self-pity,

Jealousy,

Or fear.

We see what we don't have instead of what we do.

We think things that hold us back and dampen our spirit.

But it's not just about thinking.

Our actions matter.

It takes conscious,

Consistent,

And creative effort to make a life worth living.

This podcast is about how other people keep themselves moving in the right direction,

How they feed their good wolf.

Thanks for joining us.

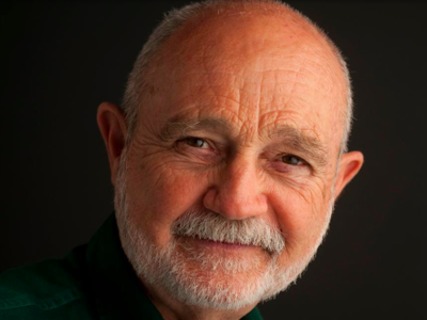

Our guest on this episode is Chuladasa,

A meditation master with over four decades of experience in the Tibetan and Theravadan Buddhist traditions.

He taught psychology and neuroscience at the Universities of Calgary and British Columbia.

Chuladasa lives in Arizona's wilderness and leads the Dharma treasure,

Buddha's Sangha.

On this episode,

Eric and Chuladasa talk about many things,

Including the book,

The Mind Illuminated.

Hi Chuladasa,

Welcome to the show.

Pleasure to be here.

Thank you for having me.

I am so excited to have you on as I told you before,

Your book,

The Mind Illuminated is one of the best books on meditation and how the mind works that I have ever read.

I've told so many people about it.

And so I think a bunch of listeners are waiting to hear this one.

So I'm really looking forward to getting into this.

But before we do,

Let's start like we always do with the parable.

There's a grandfather who's talking with his grandson.

He says,

In life,

There are two wolves inside of us that are always at battle.

One is a bad wolf,

Which represents things like greed and hatred and fear.

And the other is a good wolf,

Which represents things like kindness and bravery and love.

The grandson stops and he thinks about it for a second and looks up at his grandfather.

He says,

Well,

Grandfather,

Which one wins?

And the grandfather says the one you feed.

So I'd like to start off by asking you what that parable means to you in your life and in the work that you do.

Well,

You know,

It's very interesting,

Eric.

I would say that that parable is an extremely good description of what the Dharma practice is all about.

We have these two sides to our nature,

Which that parable describes.

And yeah,

It's which one we feed.

If we go around succumbing to greed and hatred and basically acting out of self-centeredness and selfishness,

Then that grows stronger and that comes to characterize the kind of person we are.

And as a matter of fact,

When it spreads culture wide,

We end up with the kind of world we have.

On the other hand,

If we can learn to feed the other wolf,

If we can practice loving kindness and understanding and compassion,

We can learn to maximize the cooperativity aspect of ourselves rather than the competitive aspect.

Then that's the wolf that wins.

And quite frankly,

Up until now in the history of Buddhism,

It's been all about feeding the right wolf largely for your own sake.

Although the Mahayana school has recognized that you need to go beyond that.

But we're at a place where the survival of humanity,

Or at the very least,

The survival of the incredible cultural heritage that we have developed is at very,

Very serious risk.

And the only solution that I can see is to feed the right wolf.

I agree.

I'm actually one of those people that believes the world is getting better in a lot of ways.

But I also think at the same time that it's getting better,

Our challenges are growing in magnitude.

The impact that our screw ups can have are so much worse.

The impact greed and hatred and fear can have in the world is magnified by just the nature of our technology and our tools.

I totally agree.

It's a race between these two sides of our nature and which one wins on a collective basis is going to determine the future.

That's why this Dharma has to spread beyond individuals.

So I mentioned to you before and for the listeners,

We're going to do this as a two part interview.

And we're going to do it in two sections.

The first section we're going to do is we're going to talk about your understanding of how the mind and the brain works based on different Buddhist teachings and your own experience in neuroscience.

And then in the second part,

We'll talk about applying that stuff and get very specific about meditation guidance,

Which is really one of the strengths of the book.

But the other strength is this whole section about understanding how the mind works.

And I wanted to make sure we got that.

And it's a little bit dense at points.

And I've been fretting a little bit about like,

Am I going to be able to get this,

You know,

Into a podcast and you know,

Make it digestible.

So we'll see how we go.

But I think it's worth trying.

I thought we'd start with the basic distinction between attention and awareness,

Because that is fundamental to basically everything that you teach,

Particularly the meditation stuff is understanding the difference between those two things,

And being able to recognize them.

I agree with you,

It is totally fundamental.

And when I realized the distinction between those two,

It made all of the difference in the world,

Not just to my own practice,

But to my ability to understand what people had been trying to say in all of these classic meditation texts over the centuries.

And also helped to make sense of what was going on in the world with people.

The key to it,

Initially,

Maybe this isn't the key,

This was the discovery of the keyhole.

Like so many people,

My initial meditation training led me to believe that what I was trying to do was to make my meditation object,

The breath,

The only thing that was present in my consciousness and to eliminate everything else.

And this was such a struggle,

And frustration,

Dullness and drowsiness and falling asleep and all of the usual kinds of things,

Extensive mind wandering and everything.

I find myself lost in mind wandering and then I go back to this really narrow focused perspective.

And I don't know why exactly,

But one day it occurred to me to just,

Why don't I just let all that other stuff be there.

And as long as I'm focused on my meditation object,

Let's see what happens.

And everything not only became easier,

But I could recognize the problems in my practice before they became problems.

And then,

So that was the discovery of,

Like I said,

The keyhole.

Then I found the key,

Which was when I read the descriptions that there were two different networks by which we became conscious of things in our day to day,

Moment to moment knowing of the world.

One was this aspect of our mind,

Which focused on things,

Analyze those things,

Allowed us to manipulate our experience,

Solve problems,

Do all these great things.

But there was this other aspect,

This other brain network that functioned in a different way and it took in information in a much more global or holistic way and was actually providing a completely different kind of information,

A different perspective.

And that the two were intended to work together.

And so these were being described by neuroscientists as the dorsal attentional network and the ventral attentional network.

They were most often being described as two kinds of attention,

But it was so obvious that these were inappropriate terms.

And then of course,

In cognitive science,

You're being at the end to see people using terms like focused attention and open attention or broad attention or distributed attention.

And I thought about this and I thought about the way we use language and I said,

This is an extremely important discovery and concept,

How to talk about this in a way that is meaningful.

And it occurred to me that people use the terms attention and awareness interchangeably,

Very often.

There was a lot of conflation of these two as just being two different ways of referring to the same thing.

But at a little deeper level,

There was a distinction there that was part of our common language,

Part of our common understanding.

People would selectively use the word attention or paying attention in association with words like concentration and focus and things like that.

But people would also often use the word awareness,

Not just in a broad sense to include everything,

Which was actually quite appropriate,

But also that kind of knowing that didn't involve this highly focused analytical approach to things.

And so there was what I realized is within the language itself,

There was already an intuitive understanding of these two ways of knowing,

These two ways of perceiving experience.

And that all that was really necessary was tease them apart so that we could use these words and the kind of understanding people already had in order to be able to talk about these two ways of knowing.

And it is an interesting thing about the way our minds work that when we can give labels to something,

Then we can understand them and we can use them better.

So it's a very interesting thing.

I think it goes back to some biblical references that to give a name to something is to know it or to understand it.

And if you think about it,

Like you'd say,

Of course,

A dog can pay attention to things,

But if you take a worm,

It's kind of hard to imagine an earthworm paying attention to something,

But you'd certainly say an earthworm was aware.

And where I live,

I'm surrounded by wildlife and I watched the deer and I see that deer dwell in a state of awareness and attention is something that they invoke periodically.

So as a result of all of this,

This particular distinction,

Both on a neurological,

Neurophysiological basis and the experiential basis just became really clear.

And at that point,

I could look at what had previously been confusing discussions by modern meditation teachers trying to describe what mindfulness was by the writers of traditional texts going back to early commentaries on the Buddhist teaching.

And this particular key unlocked the meaning of what they had sensed intuitively and were trying to put into words,

But without the specific language to distinguish between these two different things.

Yep.

And so in your specific definition,

And that's one of the things I love about the book,

Is you define things very,

Very clearly so that we all know what we're talking about.

And attention in your definition is the process of giving attention to one thing to sort of analyze it and learn more about it and just be focused on it.

Whereas awareness is the broader sense of what's happening around us.

So I'm sitting here talking to you,

My attention is on you and your conversation and your face here.

But my awareness knows though that there's a room behind me and there's light coming in and that somebody knocked on the door next door.

My awareness is sort of picking all that up,

But it's my attention that is what I focus on.

And one of the things I thought was so interesting about this approach,

And we'll cover it more as we get into meditation in the next section,

But this leads us into the idea of moments of consciousness.

I don't know if you called it the moments of consciousness model,

But there's a whole chapter on that idea.

Do you think you could walk us through what you mean by moments of consciousness and what that model is?

Yes.

To begin with,

The origins of this were very early meditators.

Now this is something that many meditators will experience at some point,

That they will begin to perceive their experience in the form of the rapid arising and passing away of moments of consciousness.

And interestingly enough,

This seems to happen at several different frequencies that seem to be fairly characteristic.

Well,

This had been noticed by early meditators who constructed the part of the polycanon that's called the Abhidhamma,

And they used it as a basis for taking all of the various things that the Buddha had taught about consciousness and putting it into a framework,

That consciousness consisted of individual moments of consciousness that arose and pass away.

And each moment of consciousness had specific characteristics to it.

Of course,

It had the object of consciousness,

Which is the one that we most easily become aware of.

But these wonderful meditators who created the Abhidhamma recognized and enumerated a very,

Very long list of characteristics which could be present or absent in each moment of consciousness,

And which basically determined the qualities of that moment of consciousness.

Now,

Like I say,

This is something that many meditators experience,

This arising and passing away of experience in these discrete moments.

And this is something that had been analyzed in great detail.

One of the interesting things about this from the point of view of neurophysiology is what is going on in the brain are all of these different complex waves of electrochemical activity that are going through the brain.

I think most people have enough knowledge of brain function to realize that there are all these neurons,

They're connected to each other at junctions called synapses.

And an electrical current runs along a fiber that's part of one neuron,

And at the end,

It releases a chemical neurotransmitter that stimulates the next neuron in a chain and initiates a wave of electric change that passes to the end of that neuron and to the next.

Well,

It actually turns out that individual neurons can have anywhere from dozens to literally thousands of these connections to other neurons.

And when you do a classic electroencephalogram,

You know,

EEG,

You put the electrodes on the scalp,

What you're really doing is you're tapping into the electrical part of those electrochemical waves passing through the brain.

So this is a form that information is taking in the brain.

And if you have information in the form of a wave,

What you have to do to extract the information is you have to take a chunk of that wave and you have to break it down and then you can extract its information content.

This gets down to,

You know,

Basic physics and mathematics and something that people have been doing for going on 150,

200 years,

Learning to analyze the information content of waves.

And we do this,

I mean,

The information that's being passed between you and I in all of its different forms is really in a form of a wave and it becomes digitized.

But what do we mean by digitization?

We mean you take chunks of that wave and you extract the information content.

Do you see how that understanding of that physical process of how you extract information from waves translates into the subjective experience of information in pulses or chunks or moments of consciousness?

Yeah.

So this all comes together to offer a model.

And it's a model that has a lot of utility.

And now every model is just an approximation.

Some models are closer representation of what they attempt to model than others.

But the whole purpose of a model is to help us to understand something.

So what I've done is I've taken this moments of consciousness model that historically goes back to shortly after the time of the Buddha that is common to my own meditation experience and that of many others.

And that has its counterpart in understanding how the brain works to extract information.

And I've applied it to the experience of every meditator.

Because every meditator who sits down to meditate,

To learn to meditate,

There's two things that they experience.

And there are a variety of different kinds of information.

And we can distinguish some of those as the information that we are interested in.

If you're meditating,

It's your meditation object.

If you're a student focusing on your homework,

It's your homework.

And then there's all that other information that keeps appearing in the mind that is not related to that.

So we have the phenomenon of distractions that can lead to forgetting what your primary focus is.

And the other thing we have is dullness.

And both of these things are actually inherent in the Abhidhamma description of moments of consciousness.

I just developed them for the purpose of helping the meditator have a model that's relatively easy to understand,

That they can apply to what it is they're trying to do in their practice.

Well,

I'm trying to increase the number of moments of consciousness that are on my meditation object in order to stabilize my attention.

I'm trying to increase the proportion of moments of consciousness that take the form of awareness in order to develop this other aspect of how I know so that I can use it in my meditation.

And where are these additional moments of consciousness coming from?

Well,

There's this whole supply of non perceiving potential moments of consciousness.

And of course,

This can explain dullness.

And this can explain that really high level of consciousness,

That powerful conscious perception that we all experience under certain circumstances.

So there's a continuous stream of moments of consciousness,

Ordinarily,

Many of them are non perceiving,

And those that contain information content can take a variety of forms.

So now we have a model by which we can talk about how we go from a mind that's full of distractions that can lead us to forget what we're doing and end up in the chain of mind wandering,

How it is that we can descend from the level of consciousness that we first sat down with,

In into a state of sleepiness,

Or even actual sleep.

And likewise,

How we can sit down to meditate and ascend to a very high level of conscious clarity.

And so in essence,

What you're saying is that what appears to us to be a continuous stream of consciousness are really individual moments of consciousness,

Kind of the way if you think about a movie,

Right?

It's a bunch of still frames that you just process really fast.

And that those come from in a variety of sources start from our senses.

So there's the five senses.

So those are a certain moment of consciousness.

And then the other one is that,

And I've heard this from Buddhism before about the idea of the mind or the thinking itself being a sort of a sixth sense that you watch.

And then the piece that you put in that I thought was so interesting,

I'd never really thought about or understood or read is the idea of binding moments of consciousness,

How these individual moments are happening.

They're these these things that are coming up.

And then there's another type of consciousness that is the piece that makes it look seamless.

That's right.

It's a piece that helps make it look seamless.

Yes,

Yes.

And your point is in meditation,

If people get to a deep enough level,

They begin to see the frames in a sense to use the movie analogy.

Yes,

They begin to be able to see the frames.

And the other thing is that they develop the ability to see frames of different levels of complexity.

Your mind is taking in information in a very basic fundamental form and then combining it so that by the time it comes to consciousness,

It's been highly processed,

Highly conceptualized.

So the other thing you can do is you can.

4.7 (53)

Recent Reviews

♓🐚☀️Candy🌸🦋🕊

September 24, 2019

Very insightful and the way it was presented was easy to understand. I’m looking forward to part two.

John

September 19, 2019

Much to think about! And the clarity of presentation so appreciated. Thank you!